Brazil’s Supreme Court placed former President Jair Bolsonaro under house arrest on Monday, August 4, as he faces trial for his role in orchestrating a coup to remain in power after losing the 2022 election, the most visible aspect of which was Brazil’s own insurrection on the three seats of power on January 8, 2023. Justice Alexandre de Moraes, who is overseeing the case, said the 70‑year‑old former president violated court-imposed restrictions by spreading political content online through his three sons over the weekend. Bolsonaro’s legal team said it will appeal.

The ruling, however, triggered a surge of online engagement among U.S.-based social media users – in English, Spanish, and Portuguese – and it proves that online mobilizations no longer respect national borders or languages. They rely on (online and offline) connections among key stakeholders “within the movement” or who share similar ideologies or values, to catch on fire. Politicians from Brazil and the U.S. have jumped together into the discussions, mobilizing their audiences towards their interpretations of events, which often align with their political vision or personal beliefs. The result is a widespread conversation that generates huge amounts of interactions.

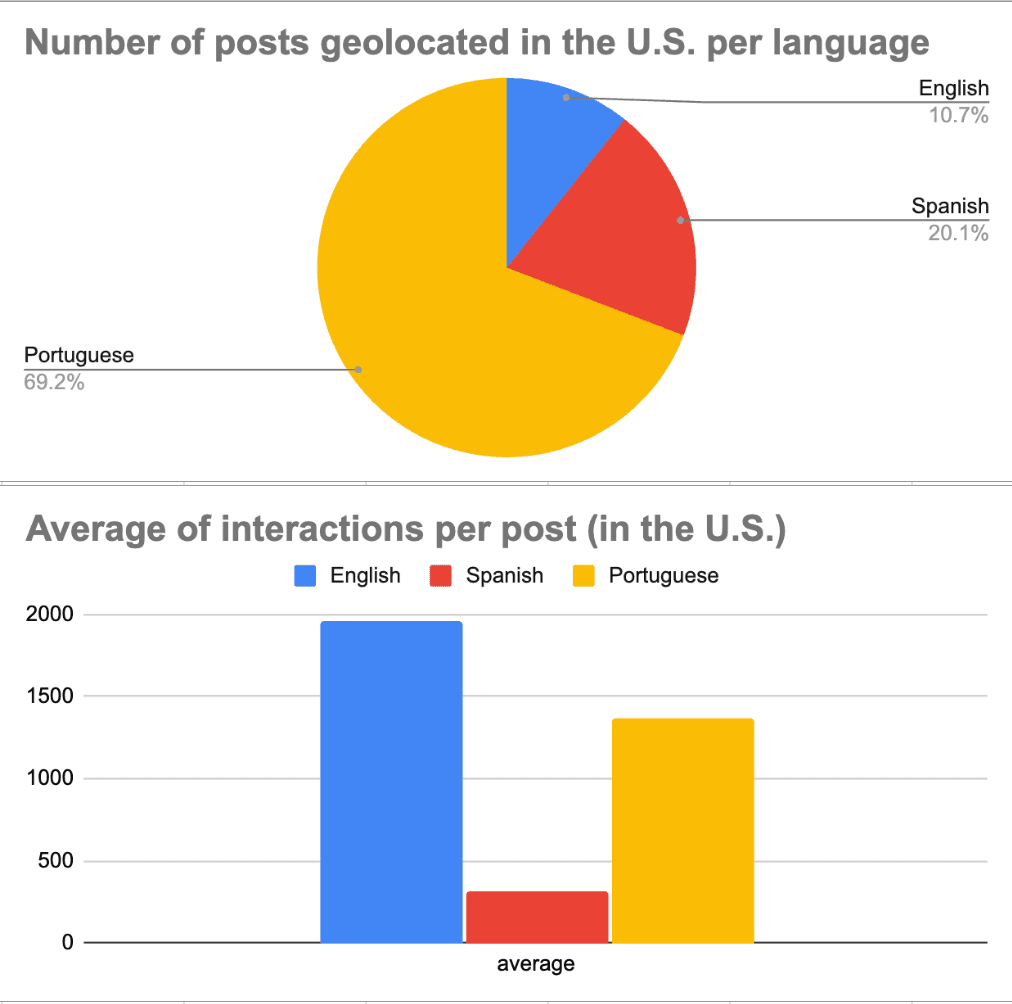

Data from NewsWhip, a tool we use to track activity across Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, X, and YouTube, shows that within 24 hours:

More than 340 English-language posts sparked 667,000 interactions.

More than 640 posts about the topic were generated in Spanish, gathering over 201,000 interactions.

More than 2,200 posts were made in Portuguese, mostly on X, drawing nearly 3 million interactions.

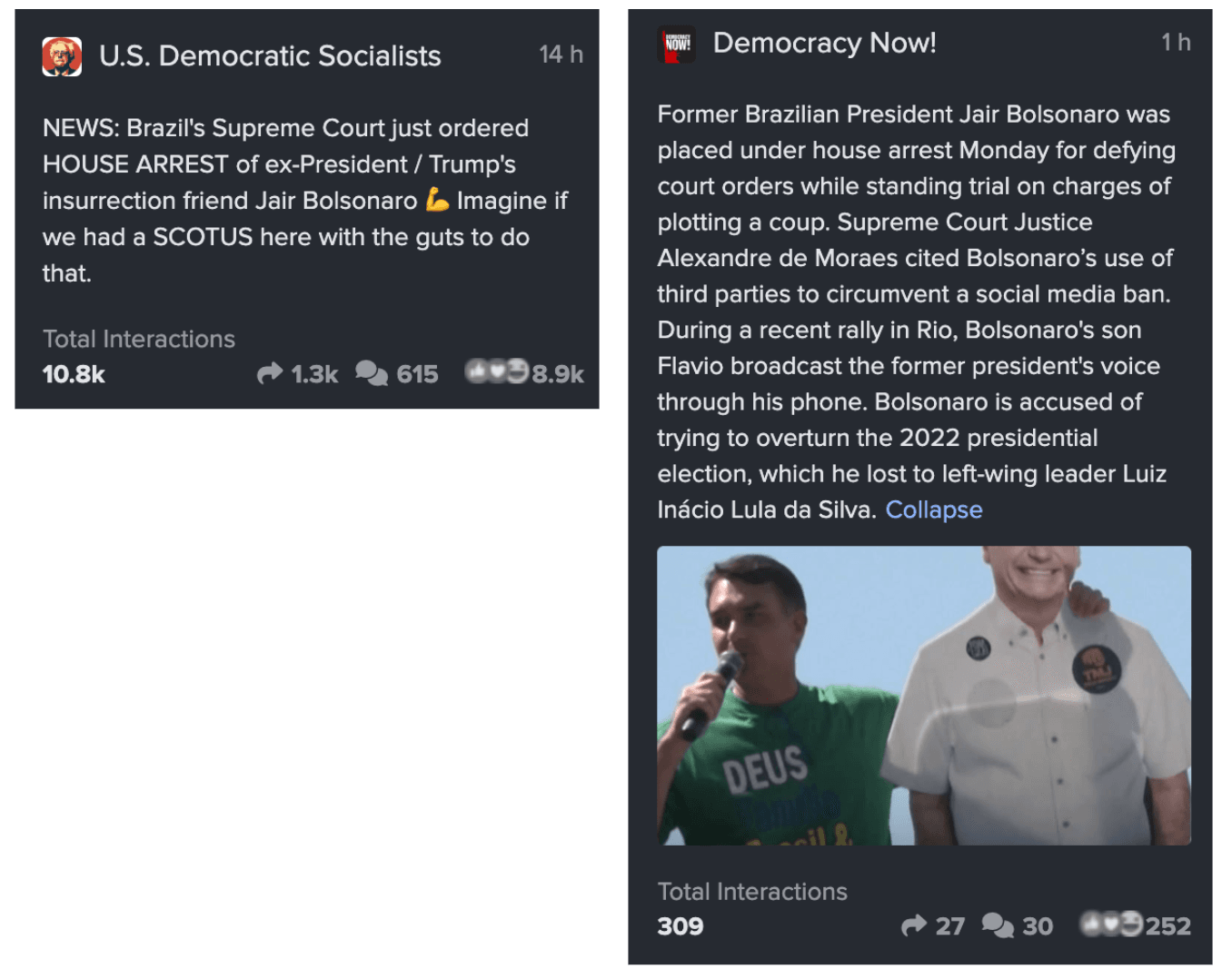

In the U.S., English-language social media publications split into two dominant narratives. Progressive voices and news media outlets cast the decision as overdue accountability, painting Bolsonaro as a coup plotter whose actions echoed Donald Trump’s efforts to remain in power. Groups like the U.S. Democratic Socialists and Democracy Now! applauded the court’s “courage,” with some users imagining a similar scenario against Trump in the United States.

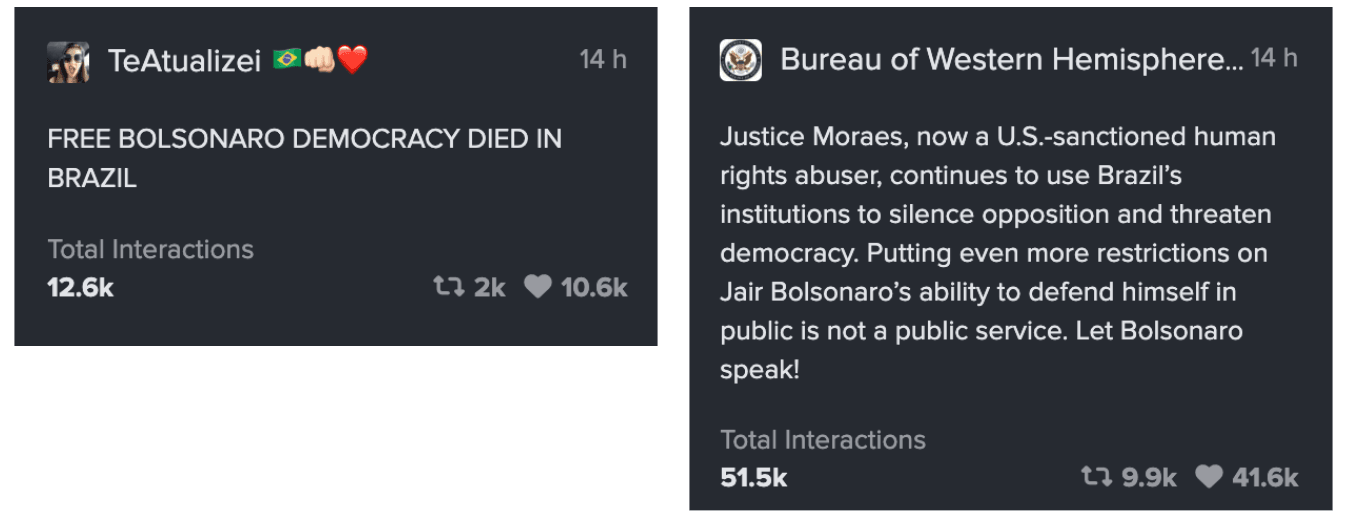

Meanwhile, a louder and more viral pro-Bolsonaro wave, underpinned by comments made by President Donald Trump, the White House, Marco Rubio and the Bureau of Western Hemisphere Affairs at the U.S. Department of State, framed the arrest as political persecution. Posts amplified by figures such as former Brazilian congressman Eduardo Bolsonaro and U.S. Representative María Elvira Salazar accused Justice Moraes of authoritarian overreach and rallied around slogans like “Free Bolsonaro” and “Democracy Died in Brazil.”

It is relevant to note that the Bureau of Western Hemisphere Affairs (part of the U.S. State Department) posted on X a very strong message against Justice the Moraes, emphasizing that he is now a U.S.-sanctioned human rights abuser (per Magnistiky Law), who supposedly “continues to use Brazil’s institutions to silence opposition and threaten democracy”.

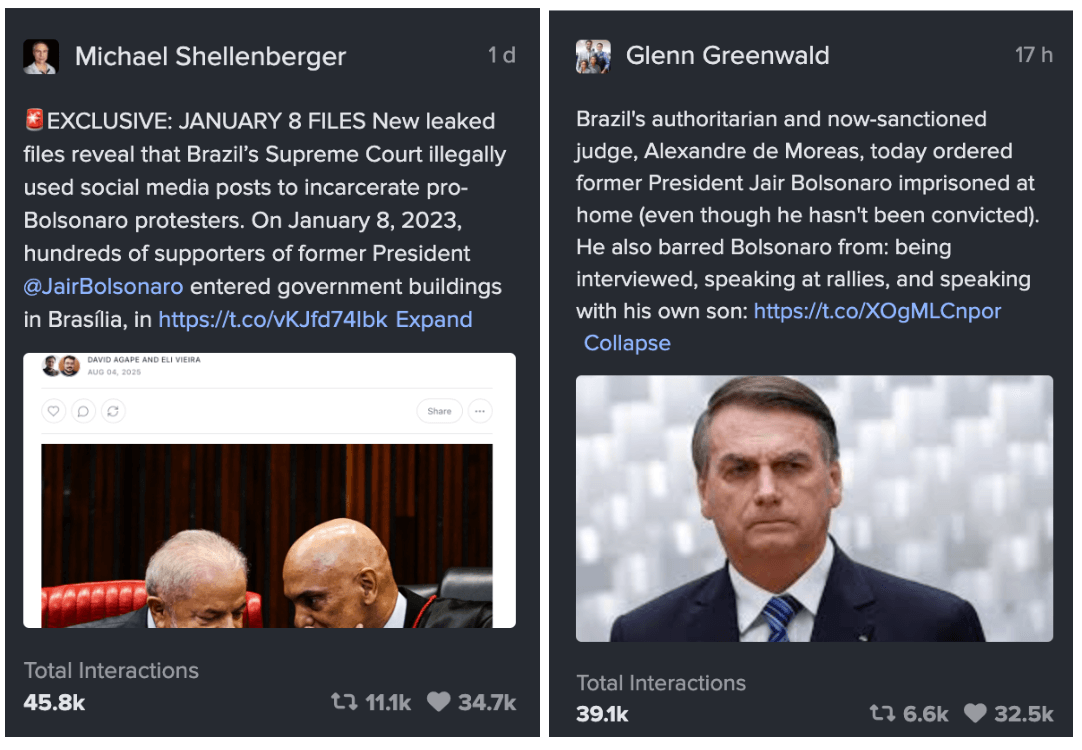

Among the English-language content, DDIA researchers also detected a subnarrative rooted in a growing global control conspiracy theory. Promoted by commentators like Michael Shellenberger and Glenn Greenwald, it claimed Bolsonaro’s arrest is part of a global “lawfare” campaign targeting right-wing leaders, drawing parallels to Trump’s ongoing legal battles and warning of coordinated efforts by “global elites.”

Viral Portuguese-language publications made in the U.S. about Jair Bolsonaro's house arrest were only detected on X and mainly amplified influential right‑wing voices such as congressman Nikolas Ferreira, governors Tarcísio Gomes de Freitas (from São Paulo) and Romeu Zema (from Minas Gerais), besides Bolsonaro’s own sons, who accuse Justice Moraes of turning Brazil into a “dictatorship.”

Our researchers could not track any major Portuguese-language content about the case that had been posted in the U.S. in support of the court's decision. Humor, however, popped up. A smaller but vocal group of users mocked the ex‑president, turning his detention into a punchline. The satirical site Sensacionalista (similar to the U.S. The Onion) joked that Bolsonaro had “finally adhered to ‘stay at home’ policy”, in reference to his anti-lockdown speeches during the pandemic.

Spanish‑language social media publications made in the U.S. about Bolsonaro's house arrest, on the other hand, mostly provided a neutral and news-centered coverage. In the first 24 hours of the decision, the pages and profiles with highest engagement were outlets like CNN en Español, EFE, and El País América.

A few of Bolsonaro’s allies and sympathetic influencers, like conservative Latino influencer Eduardo Menoni, warned (as part of a battle of narratives about “due process”) that the Brazilian Judiciary branch of power is trying to rule the country. “Brasil ya no es una democracia,” published him on X, garnering more than 12,000 interactions.

UHN Plus and other right‑leaning accounts jumped into the conversation, amplifying this message and accusing Moraes of abusing judicial power. Some shared videos of people on streets suggesting those were Bolsonaro's supporters ready to protest against Moraes.

The tone of content posted in the U.S. in all three languages echoed patterns seen in past political crises across Latin America and the United States, where accusations of judicial overreach and calls for mass mobilization have fueled polarization online. From Bolivia’s 2019 upheaval to the post‑January 6 rhetoric in the U.S., the strategy seems familiar: depict legal accountability as political persecution. In the case of Bolsonaro, this digital battle reflects not only Brazil’s internal tensions but also the way U.S.‑based Latino networks recycle and amplify narratives of resistance and victimhood for a transnational audience.