For additional resources about this poll, check out:

Context

Latinos are the largest minority group in the United States and a dominant force in U.S. politics - 36.2 million Latinos will be eligible to vote in the 2024 elections.

As November approaches, understanding how U.S. Latinos consume content online, to what extent they are resisting online harms, and the role that trust plays when it comes to engagement with misinformation and disinformation is crucial for: 1) Understanding where to focus attention and interventions, 2) Building community resilience and 3) Strengthening a healthier Internet that rewards fair participation in democracy.

To that end, in the aftermath of Super Tuesday, the Digital Democracy Institute of the Americas (DDIA) partnered with YouGov to conduct a nationally representative poll of 3,015 Latino adults that explored questions of:

Familiarity and belief in misinformation in the 2024 context,

The role of political identities and values in relation to engagement with misinformation,

Levels of trust in institutions and the electoral process, and

Perceptions about artificial intelligence’s influence in the online world.

Methodology

This poll was administered online with an entirely Latino sample from March 11 to April 26, 2024. 89% of respondents chose to complete the survey in English, and 11% in Spanish. The survey had coverage of all 50 states (plus DC), with the states with the largest Latino populations (Texas, California, Florida, and New York) accounting for 58% of the sample. Latino Democrats comprised 46% of the sample, Independents made up 20%, and Latino Republicans accounted for 28%, with the remaining respondents answering ‘unsure’. To address sample imbalances, all analyses and descriptive statistics are weighted to population targets using vendor-provided survey weights.

As part of the survey, we tested familiarity and belief in 7 broad misinformation narratives (conspiracies or hyper-partisan frames), and 15 specific false claims (left-wing, right-wing, non-partisan, and placebo claims).

Narratives - defined as an account of connected events; a story.

Democrats have won elections by resorting to fraud and electoral manipulation

Vaccines are a form of population control supported by elites and large corporations

There is a Deep State composed of shadowy political figures that is working against the public

Traditional values are being eroded by a leftist political agenda that is being implemented in schools

Russia is controlling American politics by undermining our elections and causing rifts between Americans

Corporations are all-powerful in American politics, with little room for the public to make a difference

Elites are plotting with mainstream media outlets and social media companies to censor the truth

Claims - defined as a statement or assertion.

Trump won the 2020 election

Antifa was responsible for the January 6th insurrection

January 6 was a false flag operation orchestrated by the U.S. federal government and law enforcement

Democrats are failing to secure the U.S. southern border in order to allow undocumented immigrants to vote for them in U.S. elections

Trump worked with Russians to steal the presidency in 2016

Police, not protestors, were responsible for damage to buildings during the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020

Donald Trump was named on the “Epstein List” that was released, a list featuring famous individuals who traveled with known convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein

Putin warned the U.S. to stay away from the “Israel-Hamas” war

Giving kids vaccines can cause autism

COVID-19 vaccines can lead to more serious health issues like myocarditis and infertility that would otherwise not be observed among those who catch COVID-19

Polls are being manipulated to distort public opinion

Amazon delivery drones will be supplied by the U.S. military

The U.S. government is planning on selling Alaska back to Russia to pay off the national debt

The United Nations has proposed the adoption of Global Coin, a digital currency that will unify all existing currencies

The U.S. Department of Education is planning to make an online activism course mandatory for students nationwide

Takeaways

UNCERTAINTY AND SKEPTICISM: Latinos are coming across false claims online from all sides of the political spectrum, but most are not outright believing misinformation. Uncertainty continues to dominate, and that is both good and bad.

Over 62% of Latinos surveyed either outright rejected the 15 false claims or were unsure whether they were true or false.

Just under a third of Latinos surveyed had seen and believed more misinformation on average (31% of the tested claims).

Opportunities and challenges lie with the uncertain, who while simultaneously being open to fact-based information are also increasingly skeptical about most of what they see online.

This is consistent with Equis findings from 2022.

BELIEFS IN NARRATIVES VS CLAIMS: Latinos are more likely to have deeper-held beliefs about broader conspiratorial narratives than they are about specific false claims. Most respondents were familiar with and more likely to believe in the following misinformation narratives:

“Traditional values are being eroded by a leftist political agenda that is being implemented in schools.”

(50% have seen this narrative;

among those who have seen this narrative, 42% accept it)

“There is a Deep State composed of shadowy political figures that is working against the public.”

(54% have seen this narrative;

among those who have seen the narrative, 42% accept it)

“Corporations are all-powerful in American politics, with little room for the public to make a difference.”

(57% have seen this narrative;

among those who have seen the narrative, 50% accept it)

“Elites are plotting with mainstream media outlets and social media companies to censor the truth.”

(54% have seen this narrative;

among those who have seen the narrative, 47% accept it)

CONNECTIONS BETWEEN NARRATIVES AND CLAIMS: Latinos’ belief in broader narratives form “schemas” or mental "frames" that correlate with their belief in certain claims, and open doors for them to believe in misinformation.

For example, Latinos who believe “Traditional values are being eroded by a leftist political agenda being implemented in schools” are more likely to believe false claims that Democrats encourage non-citizen voting and that Antifa was responsible for the insurrection in the U.S. Capitol.

This holds even after controlling for partisanship and ideology.

SUSCEPTIBILITY: From an accuracy standpoint alone, Latinos are NOT more susceptible to misinformation than other segments of the population, but they are underserved and overly stereotyped.

The Misinformation Susceptibility Test (MIST), a validated measure constructed by researchers at the University of Cambridge, indicates that Latinos have a similar accuracy rate to the general U.S. population in correctly identifying true and false headlines (i.e., headline discernment) - 62% vs. 66% for the general population.

Despite not being inherently more susceptible to misinformation, many other factors highlighted in this study, including partisanship and distrust play into why Latinos might see and believe misinformation.

DISCERNMENT (Accuracy in identifying true vs. false headlines):

Per MIST scores --

Older, more politically interested, and more educated Latinos are slightly better able to distinguish between factual and false headlines.

The breakdown is as follows:

18-29-year-olds: 60% accuracy;

30-44-year-olds: 62% accuracy;

45-54-year-olds: 61% accuracy;

55-64-year-olds: 65% accuracy;

65+-year-olds: 68% accuracy.

Despite being generally more accurate in differentiating between factual and false headlines, politically interested individuals accept more false claims “in the wild” when they come across them online.

Why?

It could be that greater exposure to misinformation overwhelms their discernment abilities.

It could also be that the more you see something, the more you believe it to be true.

This points to the importance of supply-side factors driving misinformation adoption.

Latino Republicans, more extreme partisans, and those who consume Spanish media and information were less able to discern between factual and false headlines.

PRIORITY GROUPS FOR SOLUTIONS: Tailoring interventions and counter-disinformation strategies to those who are uncertain about what they are seeing is crucial in combating misinformation within the Latino community.

Though psychological variables and media consumption are much more significant in predicting whether someone will engage with misinformation than standard demographics, the below are notable characteristics to consider in targeting:

Women, Facebook users, Spanish-dominant, and those who consume more broadcast news and Spanish-language media are more likely to fall into the uncertain category, what we call the “higher-priority category.” They should be targeted with fact-checks and prebunks.

Focusing proactive communication efforts on platforms like YouTube is beneficial, as a majority of Latinos consume media on these platforms.

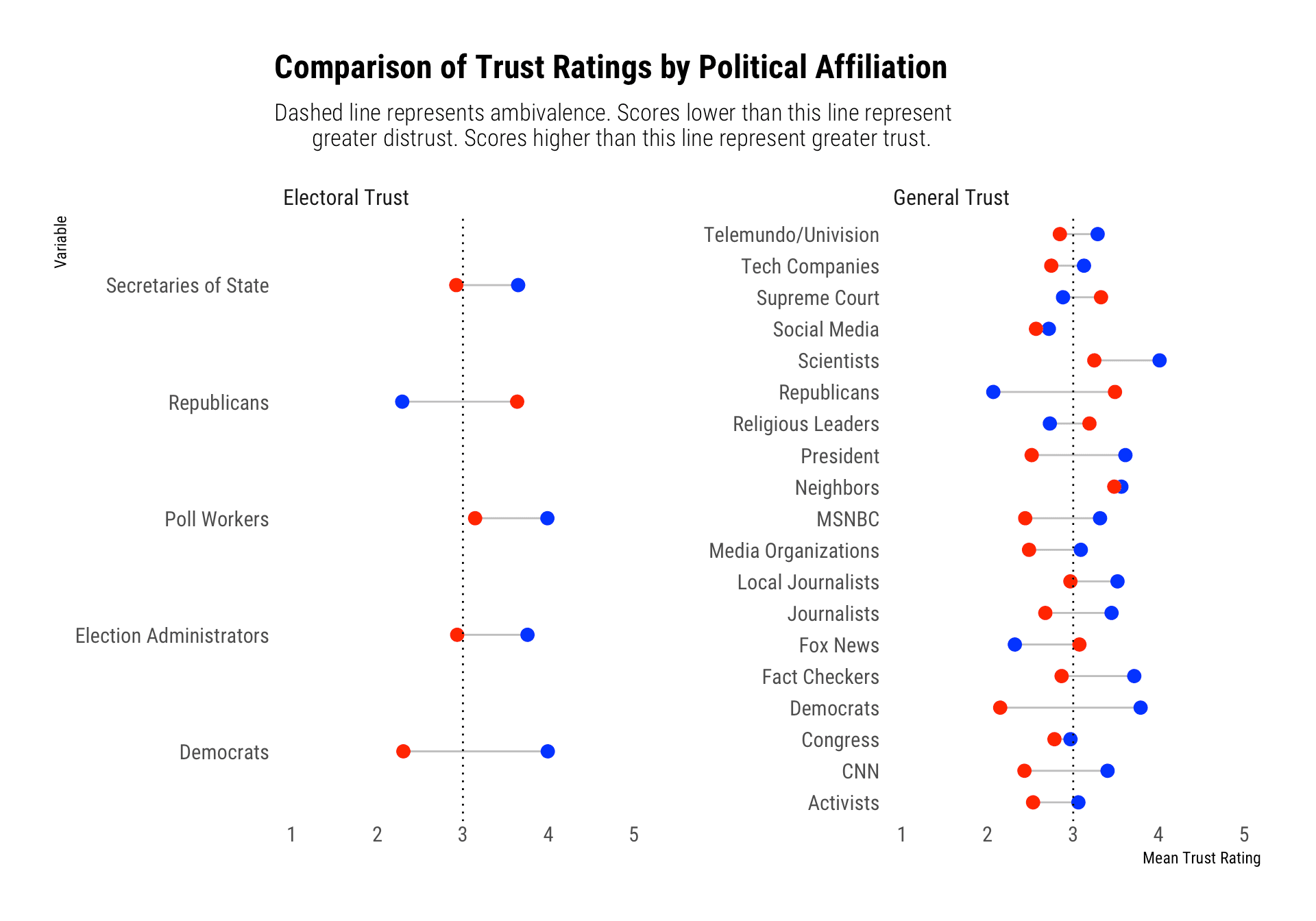

TRUST IN ELECTION OFFICIALS: Latinos’ trust in election officials is strongly correlated with partisanship and adoption of misinformation.

Latino Democrats are more likely to trust election officials such as poll workers and secretaries of state, while Latino Republicans largely express ambivalence about these actors.

The most partisan Latinos on both sides of the spectrum generally distrust the other side’s handling of elections.

TRUST IN OTHER ACTORS: Latinos’ trust in a broader set of social and political groups, including tech companies, fact-checkers, journalists, scientists, and media organizations is also correlated with partisanship.

Latino Democrats are largely ambivalent about tech companies, whereas Latino Republicans lean toward distrust.

Democrats lean toward trusting fact-checkers and local journalists, whereas Latino Republicans express ambivalence about these groups.

Scientists emerge as the only group that is trusted by both Latino Republicans and Democrats, albeit to different degrees.

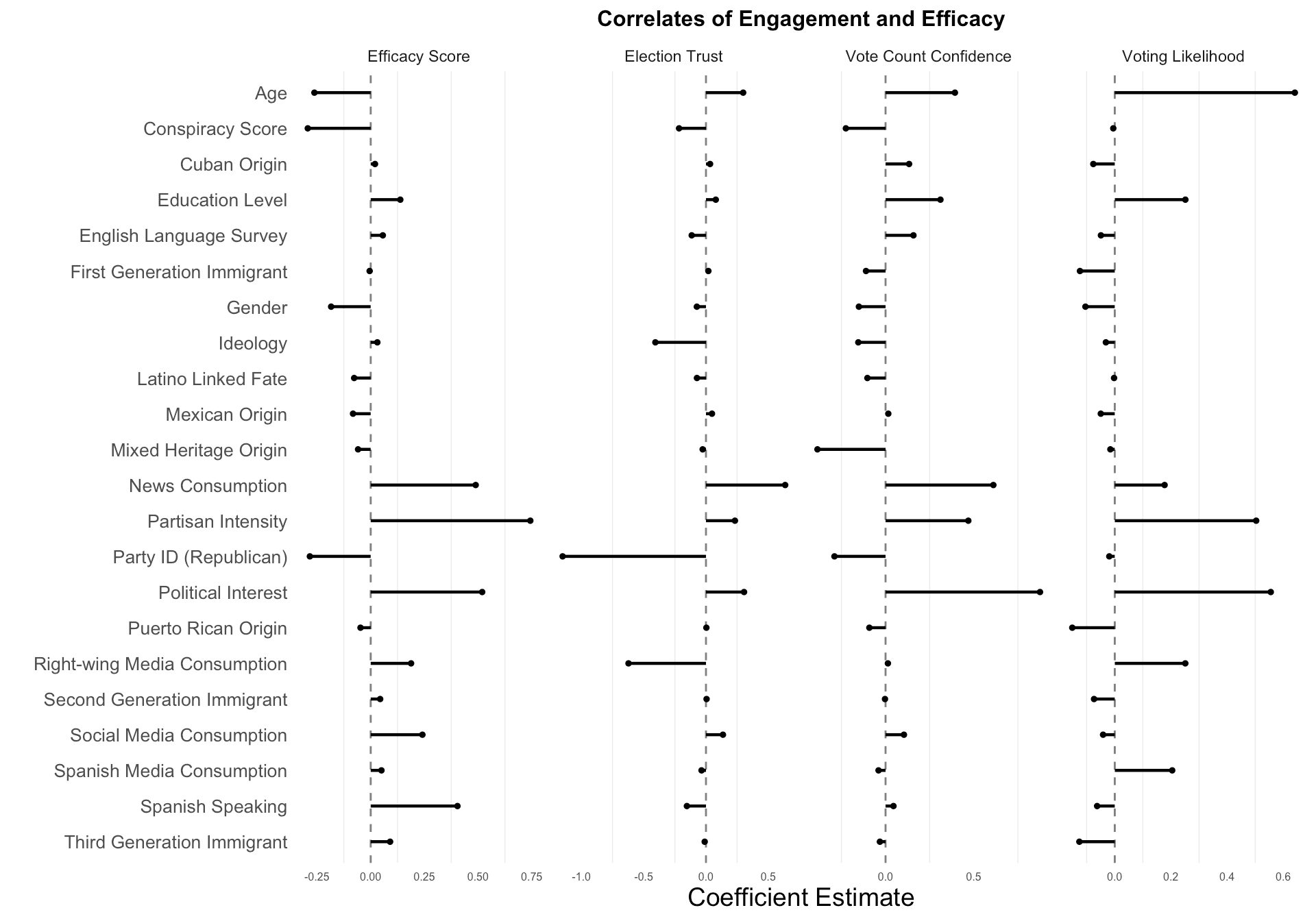

TRUST AND POLITICAL EFFICACY: Latinos with stronger partisan identities report feeling like they can have higher political impact (efficacy) in elections.

Older respondents, women, Republicans, and those with higher levels of conspiratorial views report lower efficacy.

Many of these same subgroups also distrust election officials and have doubts about whether their votes will be properly counted.

Yet, some individuals who distrust the political system and report lower levels of efficacy still report an intention to vote in 2024, indicating participation can occur even with doubts about the political process.

TRUST AND TURNOUT: For some groups, participating in elections may not hinge on whether they trust the political process. Some Latinos choose to participate in spite of beliefs of “rigged elections” or untrustworthy officials.

Partisanship and conspiratorial orientations contribute to feelings of distrust in democratic processes among Latinos.

Republican party affiliation consistently predicts lower levels of trust and confidence that one’s vote will count.

Interestingly, however, trust in the process does not necessarily influence turnout. For example, older Latinos above the age of 65 are less likely to perceive their participation in elections to matter relative to those who have recently reached voting age (ages 18-29), but are more likely to report a desire to turnout to vote.

Latinos with higher levels of conspiratorial orientation also predict lower efficacy, trust, and confidence that one’s vote will be counted. However, these factors don’t seem to have a strong association with whether they report wanting to turnout or not to vote.

ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE: Most Latinos are not yet using AI in their day-to-day lives. Latinos surveyed are broadly uncertain about AI’s impact on society, though many have significant concerns about AI’s potential for job displacement

The 15% of Latinos who reported regularly using tools like ChatGPT tended to have a more positive outlook on AI’s benefits but still support regulation to mitigate potential negative impacts.

A majority see AI’s political impact as either marginal or non-existent, with 41% agreeing that “The 2024 election will look just like every other election” and 31% viewing AI as playing a minor role through chatbots and personalized information.

Only 28% agree that AI could be a “game-changer” in the 2024 election.

Exposure, Belief, and Uncertainty in Claims and Narratives

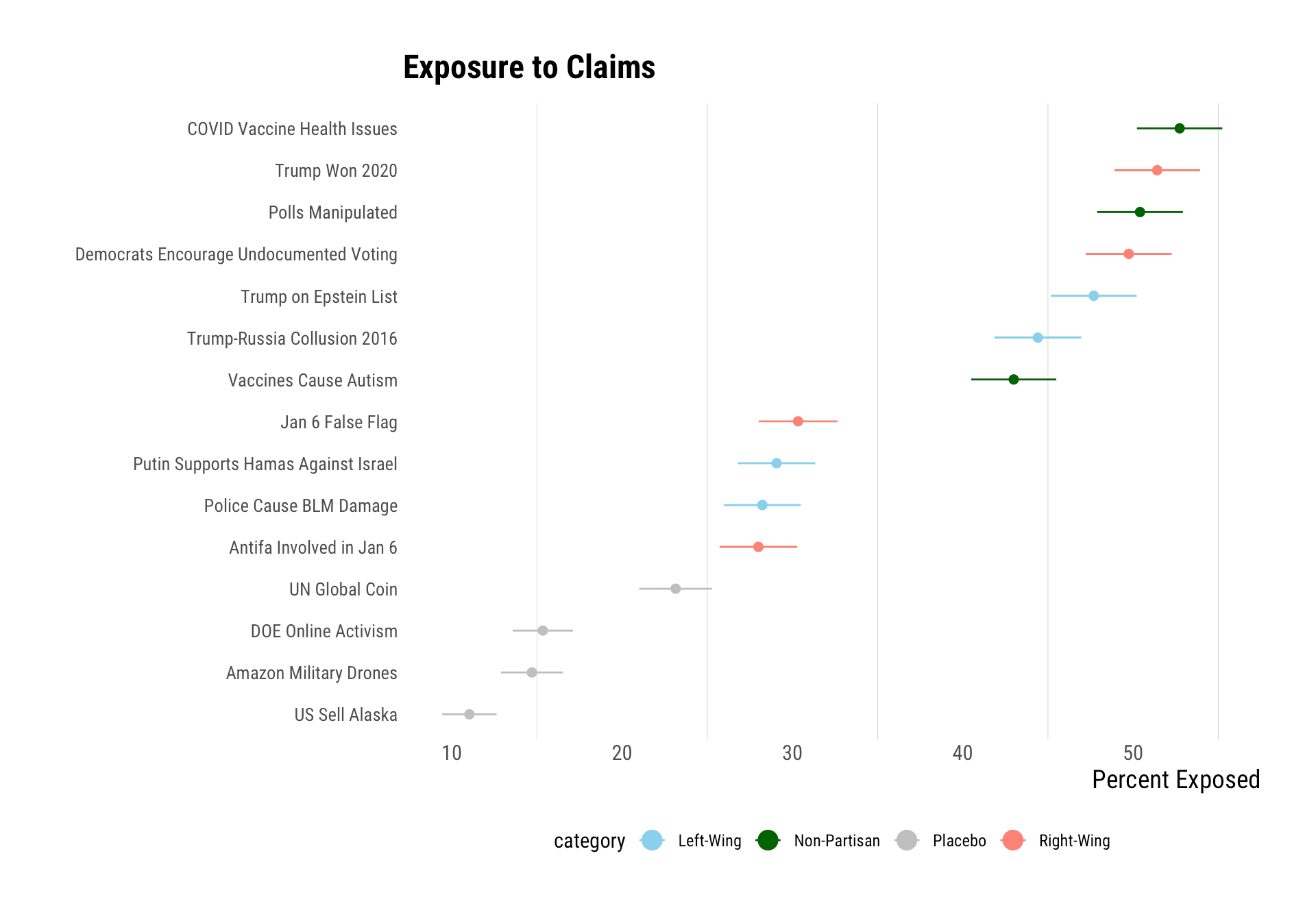

Latinos in our survey reported their exposure to various false or misleading broader claims and narratives, including a set of claims from a 2022 study on Latino misinformation conducted by Equis, and novel claims identified by DDIA’s narrative monitoring team.

Claims

The 15 claims covered political and scientific topics. We also created “placebo claims” that were not circulating online to serve as a benchmark.

Exposure was measured first, followed by belief on a 1-7 scale, with:

1-2 indicating high / moderately high certainty that a claim was false,

3 suggesting it “could be” false,

4 indicating complete uncertainty,

5 suggesting it “could be” true, and

6-7 indicating high / moderately high certainty that a claim was true.

Both exposed and unexposed respondents were asked about their belief in the accuracy of each claim.

Overall, although most Latinos in the sample were familiar with various false claims, they largely either rejected or expressed uncertainty about whether the claims were true or false. Most were not outright accepting misinformation. Latinos expressing uncertainty outnumbered those accepting specific claims 69% of the time.

Rates of Exposure/Familiarity:

High-salience claims: Over 40% of Latinos reported being familiar with the following false claims:

“COVID-19 vaccines can lead to more serious health issues like myocarditis and infertility that would otherwise not be observed among those who catch COVID-19”

“Trump won the 2020 election”

“Polls are being manipulated to distort public opinion”

“Democrats are failing to secure the U.S. southern border in order to allow undocumented immigrants to vote for them in U.S. elections”

“Donald Trump was named on the “Epstein List” that was released, a list featuring famous individuals who traveled with known convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein”

“Giving kids vaccines can cause autism”

Medium-salience claims: Around a third of those in the sample reported being familiar with the following false claims:

“Antifa was responsible for the January 6th insurrection”

“Putin warned the U.S. to stay away from the “Israel-Hamas” war”

“Police, not protestors, were responsible for damage to buildings during the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020”

“January 6 was a false flag operation orchestrated by the U.S. federal government and law enforcement”

“The United Nations has proposed the adoption of Global Coin, a digital currency that will unify all existing currencies”

The remaining items, all “placebo” claims, had been seen by fewer than 15% of the sample. The data indicate that a majority or near-majority of Latinos had seen about eight of the 15 false claims (that did not include the placebo claims).

Figure 1. Percentage of Latinos in our sample who reported being exposed to each claim.

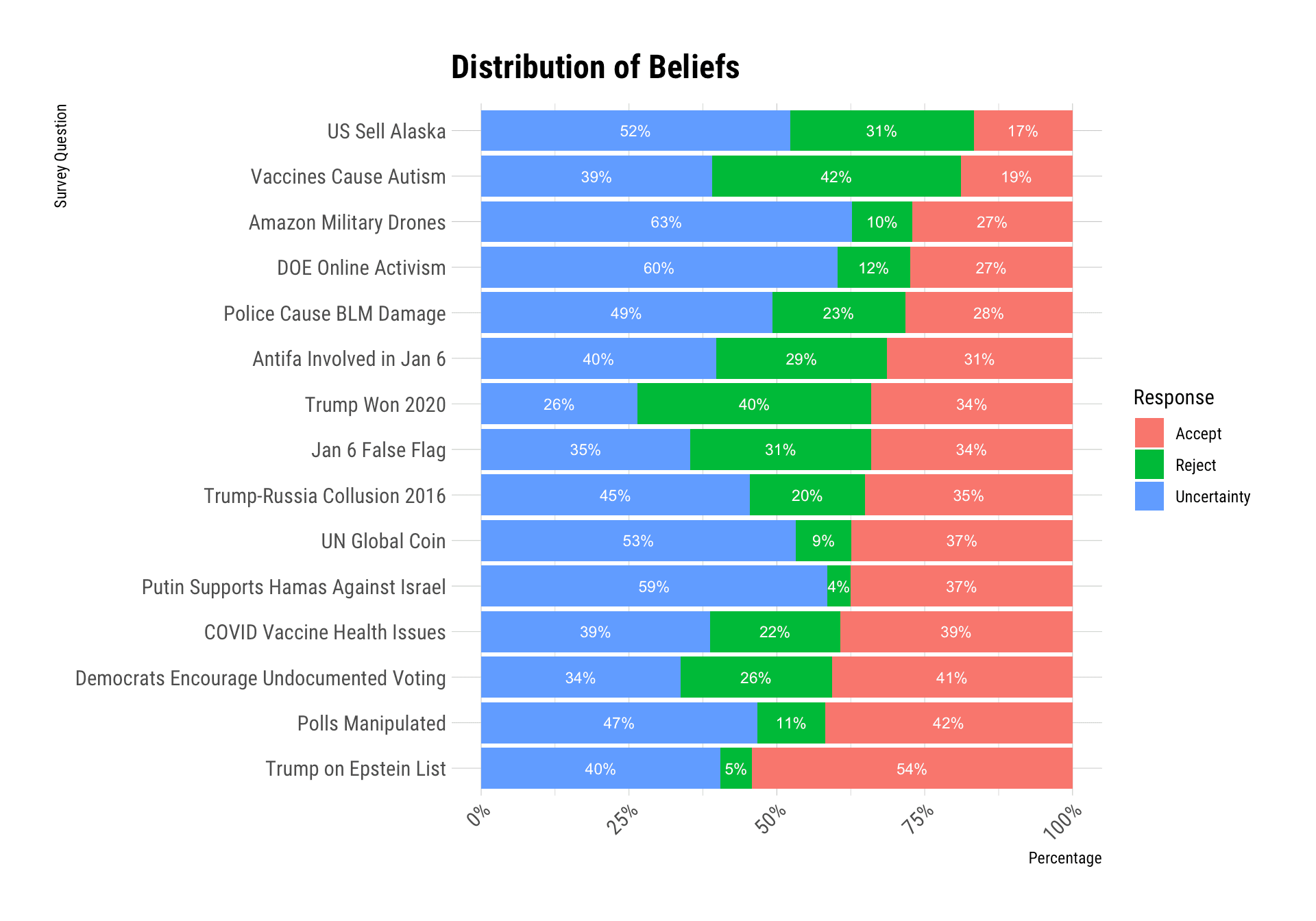

Rates of Belief Among the Exposed

Belief in misinformation varied widely among those exposed to the false or misleading claims.

The most widely accepted claim was that “Trump was on ‘Epstein’s list’” with 54% of those who had seen the claim believing it. The most widely rejected claims included “vaccines cause autism” and “Trump won in 2020.” Between 40% and 42% of our sample who had seen these claims rejected them.

Notably, in accordance with findings from the Equis 2022 misinformation poll, the most widely seen claims, like the two above, were also the most likely to be rejected.

Figure 2. Distribution of beliefs among those exposed to each claim. Blue bars indicate the percentage of those exposed who reported being uncertain. Red bars represent the percentage who accepted the claim. Green bars represent the percentage who rejected the claim.

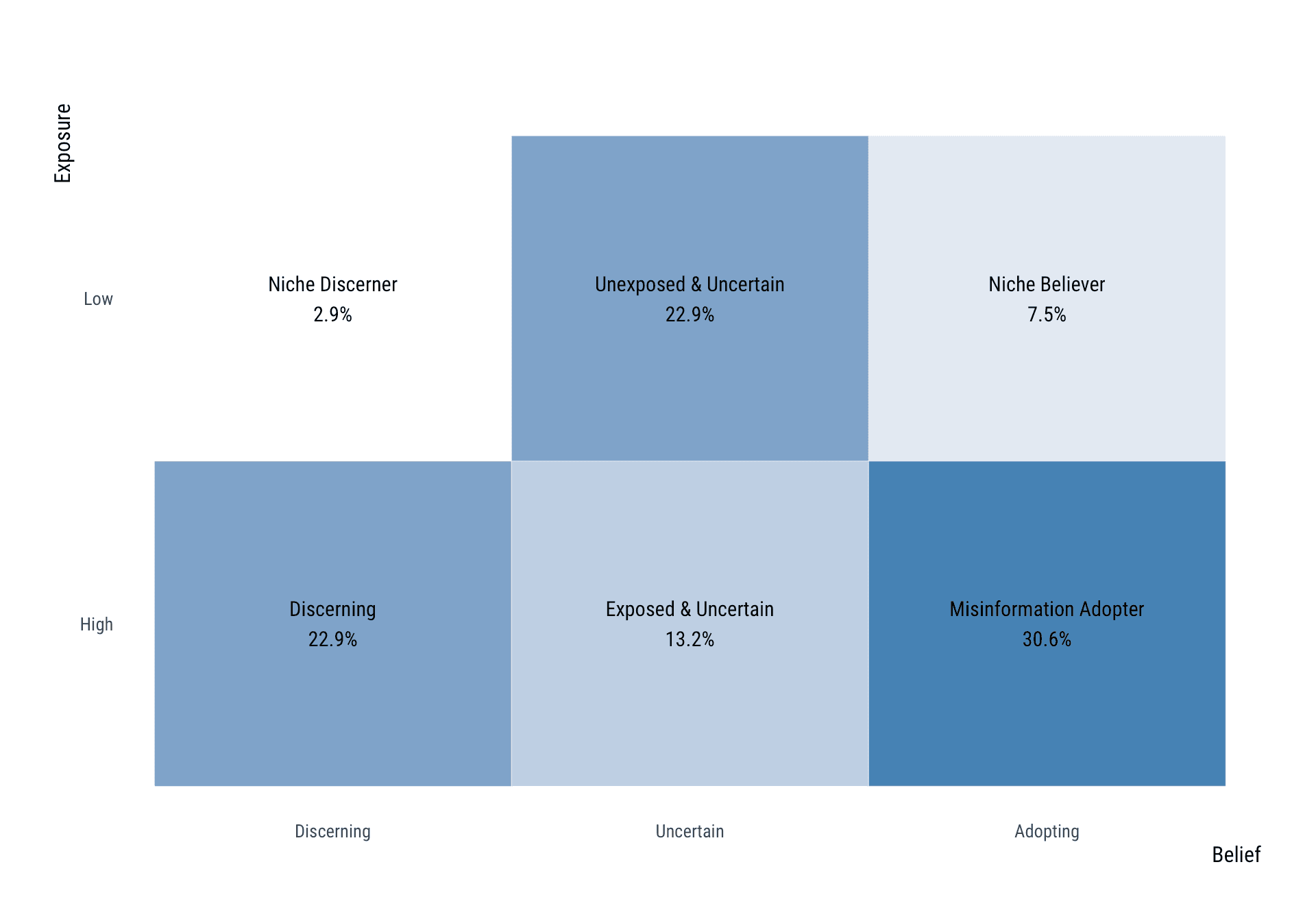

As in our 2023 DDIA analysis of the Equis poll, we segment the sample into six categories based on exposure (below-average exposure, above-average exposure) and belief (rejecting more seen claims, uncertainty, and accepting more seen claims).

Though 38% of those in our sample can be defined as either “misinformation adopters,” who have seen more misinformation and accept it, or “niche believers,” who have not seen a great deal of misinformation but accept what they have seen, 62% are either uncertain or discerning.

This means that the majority of individuals are not readily accepting misinformation, indicating a more critical approach to the information they encounter.

Figure 3. Distribution of Latinos belonging to different subgroups in the DDIA typology. The x-axis ranges from discernment to adoption, the y-axis ranges from lower to higher exposure.

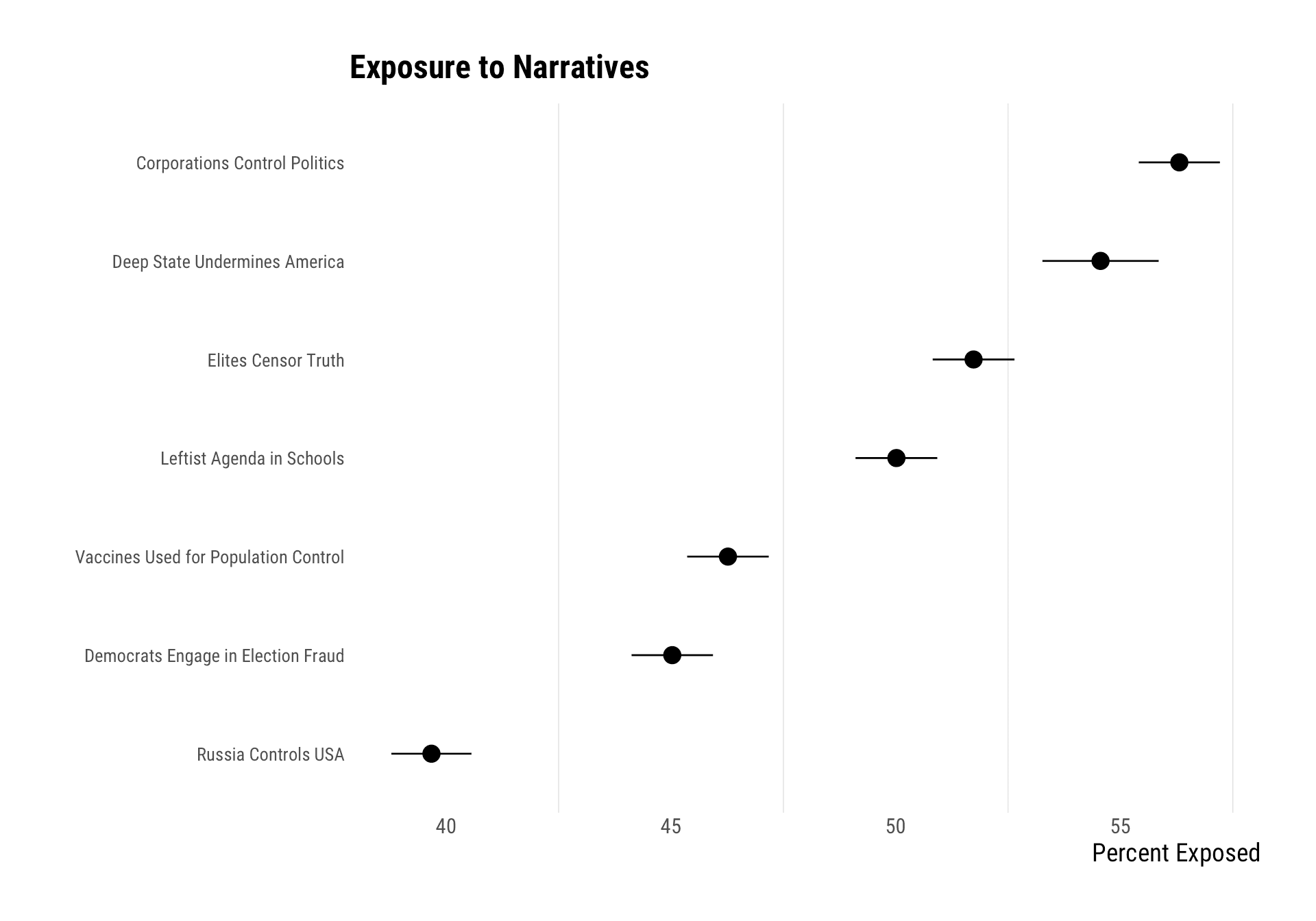

Narratives

The survey also aimed to capture beliefs in broader political narratives that may influence the acceptance of false or contested claims about discrete events. While these narratives may contain a grain of truth that we see being twisted or decontextualized in narrative analysis, measuring them helps us consider "schemas," “worldviews,” or standing positions on how politics works that enable people to more easily bring false claims into their belief systems.

Belief in these narratives may also contribute to higher levels of distrust and reduced efficacy, as they relate to larger forces influencing politics that may limit individuals' ability to affect the political system. Such narratives may lead to reduced political engagement.

The two-step procedure of measuring exposure and belief was repeated for these narratives.

Rates of Exposure/Familiarity:

DDIA tested seven narratives. Poll findings show that Latinos have high levels of familiarity with popular left- and right-wing narratives, such as “corporations control politics,” “there is a leftist agenda being implemented in schools,” and a “"Deep State" is undermining America.” Exposure to these narratives ranges from 40% for the claim that “Russia controls the U.S.” to 58% for “corporations control politics.” These exposure levels are similar to those of the “high salience” claims, such as "Covid-19 causing health issues" and the 2020 election being “stolen,” suggesting that narratives generally rival some of the most popular pieces of misinformation online.

Figure 4. Percentage of Latinos in our sample who reported being exposed to each narrative.

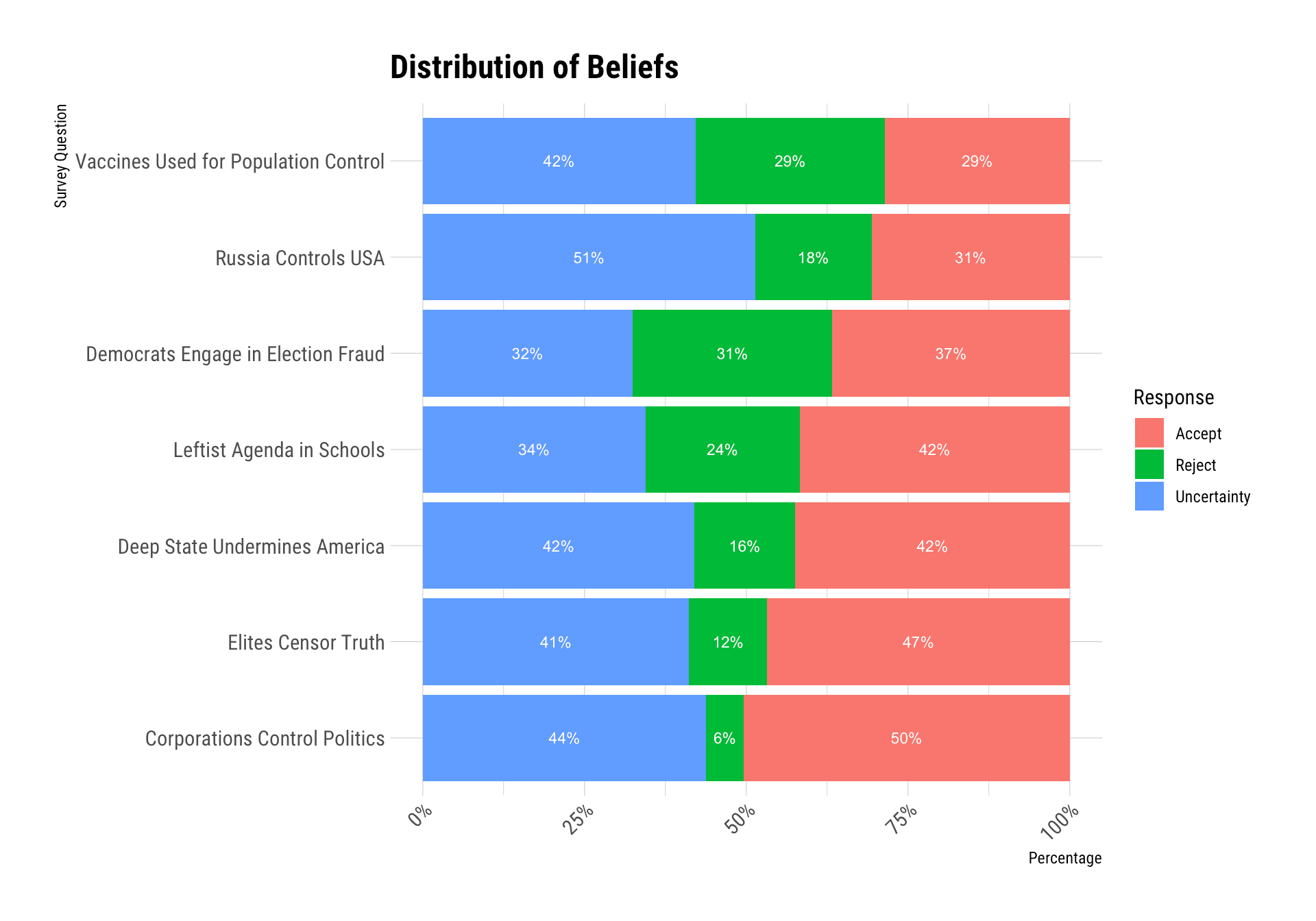

Rates of Belief Among the Exposed:

A majority or near-majority of Latinos in our sample who have seen each narrative believe that “corporations control politics” and “elites censor the truth.”

Approximately 40% believe that a “deep state undermines America,” “there is a leftist agenda in schools,” and “Democrats engage in electoral fraud.”

Similar to the case of claims, many Latinos in our sample express uncertainty around these narratives, with estimates ranging from 32% for the election fraud narrative to 51% for the Russian control narrative. However, more Latinos outright accept than outright reject these broader narratives. Our hypothesis is this shows a growing level of distrust among Latinos in elites and institutions.

Figure 5. Distribution of beliefs among those exposed to each narrative. Blue bars indicate the percentage of those exposed who reported being uncertain. Red bars represent the percentage who accepted the narrative. Green bars represent the percentage who rejected the narrative.

The Relation Between Narratives and Claims

These poll’s findings suggest that the adoption of certain narratives may influence belief in specific claims. Beliefs in broader narratives may provide organizing schemas that allow individuals to more readily accept an array of claims that align with that perspective.

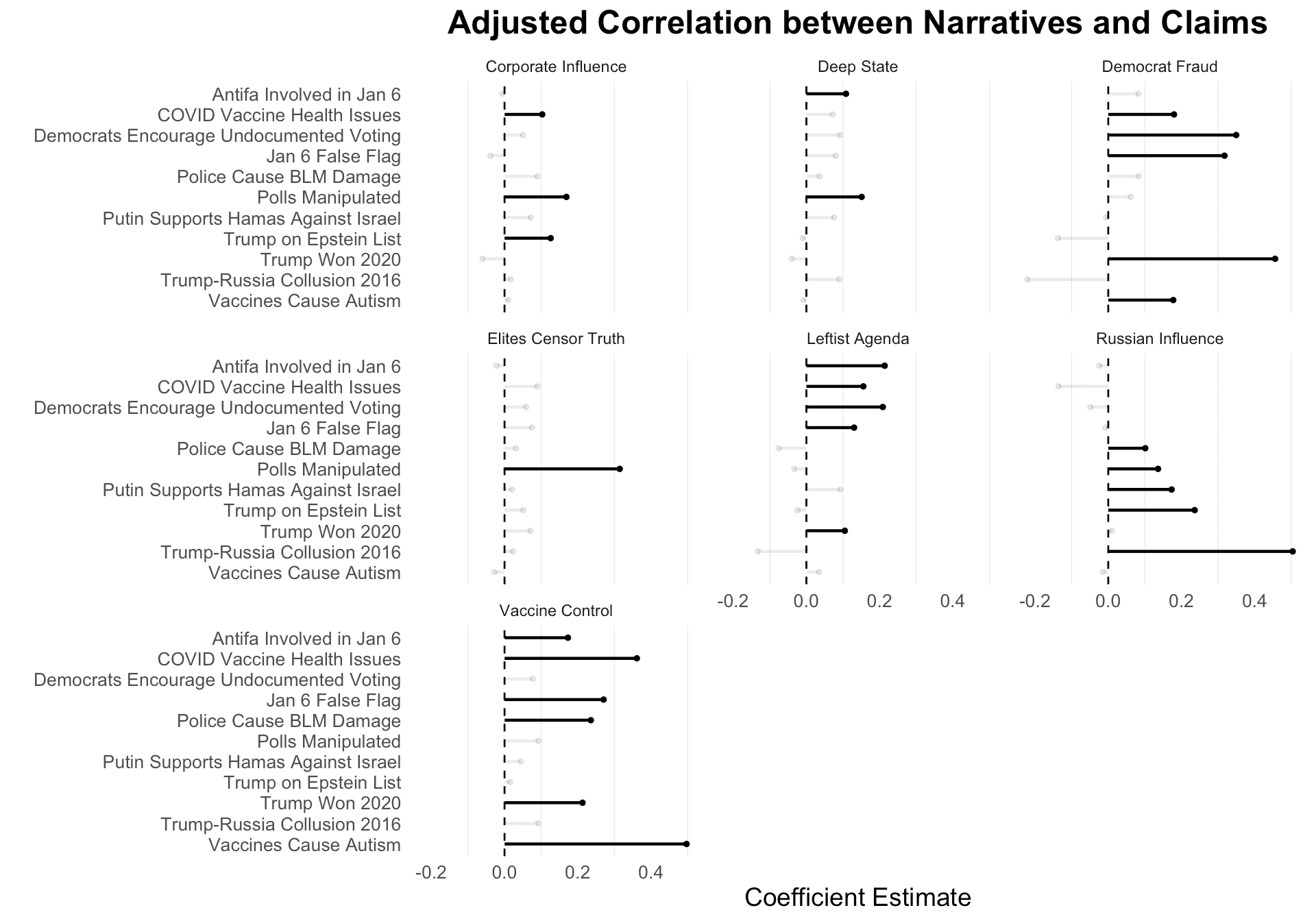

The analysis below examines the adjusted statistical association between narratives and beliefs in discrete claims, accounting for ideology and partisanship. Essentially, those who accept the narratives below are statistically more likely to believe the listed claims.

The “Corporate Influence” narrative is most strongly associated with the claims:

“COVID-19 vaccines can lead to more serious health issues like myocarditis and infertility that would otherwise not be observed among those who catch COVID-19.”

“Donald Trump was named on the “Epstein List” that was released, a list featuring famous individuals who traveled with known convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein.”

“Polls are being manipulated to distort public opinion.”

This suggests that individuals who believe that corporations control politics are more likely to accept anti-elite claims. Similarly, the “Deep State” narrative is linked with beliefs that “Antifa was involved in January 6th” and “polls are manipulated.”

The “Election Fraud” narrative shows the strongest associations with:

“Trump won the 2020 election.”

“Democrats are failing to secure the U.S. southern border in order to allow undocumented immigrants to vote for them in U.S. elections.”

“Antifa was responsible for the January 6th insurrection.”

“COVID-19 vaccines can lead to more serious health issues like myocarditis and infertility that would otherwise not be observed among those who catch COVID-19.”

The “Leftist Agenda in Public Schools” narrative is associated with:

“Democrats are failing to secure the U.S. southern border in order to allow undocumented immigrants to vote for them in U.S. elections.”

“Antifa was responsible for the January 6th insurrection.”

The “Russian Influence” narrative has the strongest correlation with:

“Trump worked with Russians to steal the presidency in 2016,” but its associations with other claims are considerably weaker.

Lastly, the “Vaccines for Population Control” narrative is most strongly associated with:

“Giving kids vaccines can cause autism,”

“COVID vaccine health issues (see above),”

and a range of other right-wing claims.

Figure 6. Regression coefficients from linear regression models including partisanship, ideology, and belief in each narrative as predictors. Each covariate is rescaled to range from zero to one. Black bars indicate statistically and substantively significant coefficients, whereas gray bars indicate variables that do not meet these criteria. Each model regresses measures of belief in a given claim on belief in a narrative, with partisanship and ideology as covariates.

Predicting Discernment, Exposure, Belief, and Uncertainty

Though most of our survey focused on Latinos’ familiarity with and belief in real-world misinformation, social psychologists have also found that belief in misinformation can be reliably predicted by discernment tests that ask participants to identify which headlines are true or false from a pool of headlines.

Half of our sample completed a validated scale constructed by researchers at the University of Cambridge called the Misinformation Susceptibility Test (or MIST for short). Scores are constructed by calculating the share of correct answers (pairing true headlines with true ratings, and false headlines with false ratings).

Latinos in our sample had an accuracy score of 62% on the MIST, which is just a few points lower than the average score in nationally representative surveys of Americans (66%). Thus, by and large, Latinos exhibit similar accuracy rates when compared to the rest of the population.

Since everyone sees the same headlines, the MIST is useful because it allows us to study how subgroups vary in discernment, irrespective of exposure. It thus serves as a useful proxy of what people might do when they encounter misinformation “in the wild.”

In addition to the MIST, we consider factors that predict exposure, belief, and confidence.

Exposure is measured as the total number of claims that a person has seen, belief is measured as the total number of claims that they have adopted, and confidence captures how often people express confidence in their beliefs (versus uncertainty), regardless of whether they are rejecting or accepting a claim.

(We estimate multiple regression models that adjust for various predictors of these factors to obtain a clearer understanding of the different elements of the misinformation process.)

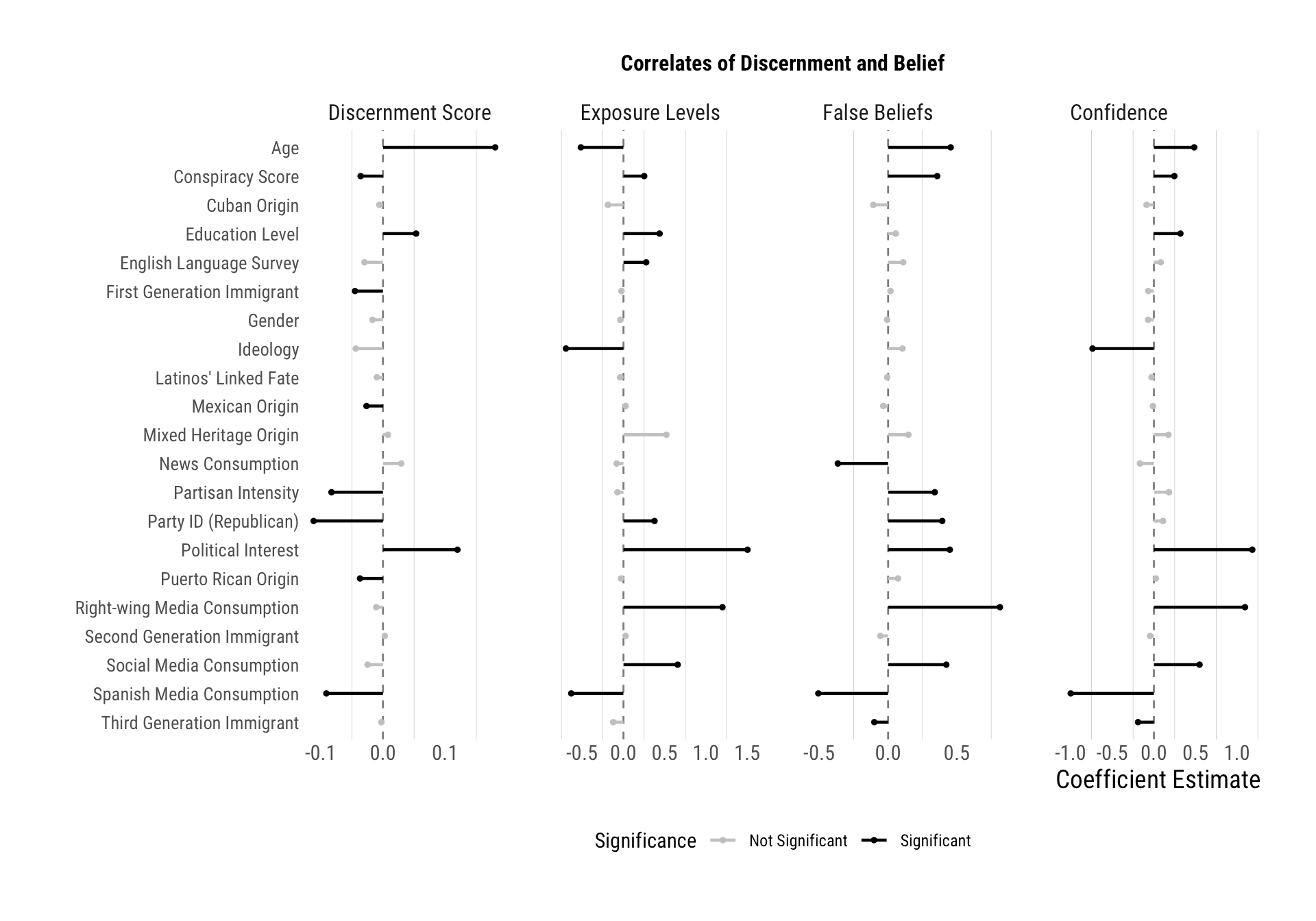

Which Latinos are Most Likely to be Discerning?

Older Latinos are more able to differentiate between true and false content, aligning with findings from the general population.

Latinos who report having high levels of political interest and education also showed higher levels of being able to discern between true and false content.

On the other hand, Republican partisanship, partisan intensity, and Spanish media consumption were associated with lower levels of discernment.

Which Latinos are Most Likely to be Seeing Misinformation?

High political interest and media consumption patterns are the most important predictors of exposure to false claims online.

The more politically interested Latinos are, the more likely they are to see misinformation.

Right-wing news and social media consumption also predict increased exposure to misinformation, whereas consumption of Spanish-language media predicts lower levels of exposure to misinformation.

Older Latinos are less likely to see false claims online in comparison to younger Latinos.

Which Latinos are Most Likely to Believe Misinformation?

Older respondents are more likely to believe the false claims they have seen, despite their higher discernment abilities. This discrepancy may be attributed to their higher levels of certainty - older people tend to be more confident in their responses, whether they are accepting or rejecting a claim. They express more conviction and less uncertainty in the veracity of claims than their younger counterparts.

Other predictors of belief in false claims include right-wing media consumption, social media consumption, high political interest, and conspiratorial orientations.

Though Spanish-language media consumers tend to see less misinformation and consequently adopt fewer false beliefs, they also score lower on discernment, which means higher exposure to misinformation as the election nears could lead to greater belief in misinformation for this group.

Though confidence might explain why older Latinos score higher on discernment yet adopt more false beliefs, discrepancies in other subgroups could be due to exposure.

For instance, individuals with high political interest are generally more discerning but also adopt more false beliefs, likely because they encounter a large volume of political information in their media environments. Consequently, even though they have a more discerning predisposition, greater exposure to false claims may cause some of these claims to "slip through" and be accepted.

This highlights the supply-side aspect of misinformation, which is beyond the control of individuals and emphasizes the need to address the prevalence of false information in the media ecosystem

Figure 7. Standardized regression coefficients from linear regression models adjusting for all of the listed variables. Each covariate is rescaled to range from zero to one. Black bars indicate statistically and substantively significant coefficients, whereas gray bars indicate variables that do not meet these criteria. Four separate models are estimated, regressing each outcome on the set of covariates.

Allocating Resources in the Fight against Latino-Targeted Misinformation

A one-size-fits-all approach to combating misinformation within the Latino community is unlikely to succeed due to the significant variation in baseline levels of discernment, information environments, and political beliefs. Therefore, it is crucial to tailor strategies to address the needs of different subgroups within this community.

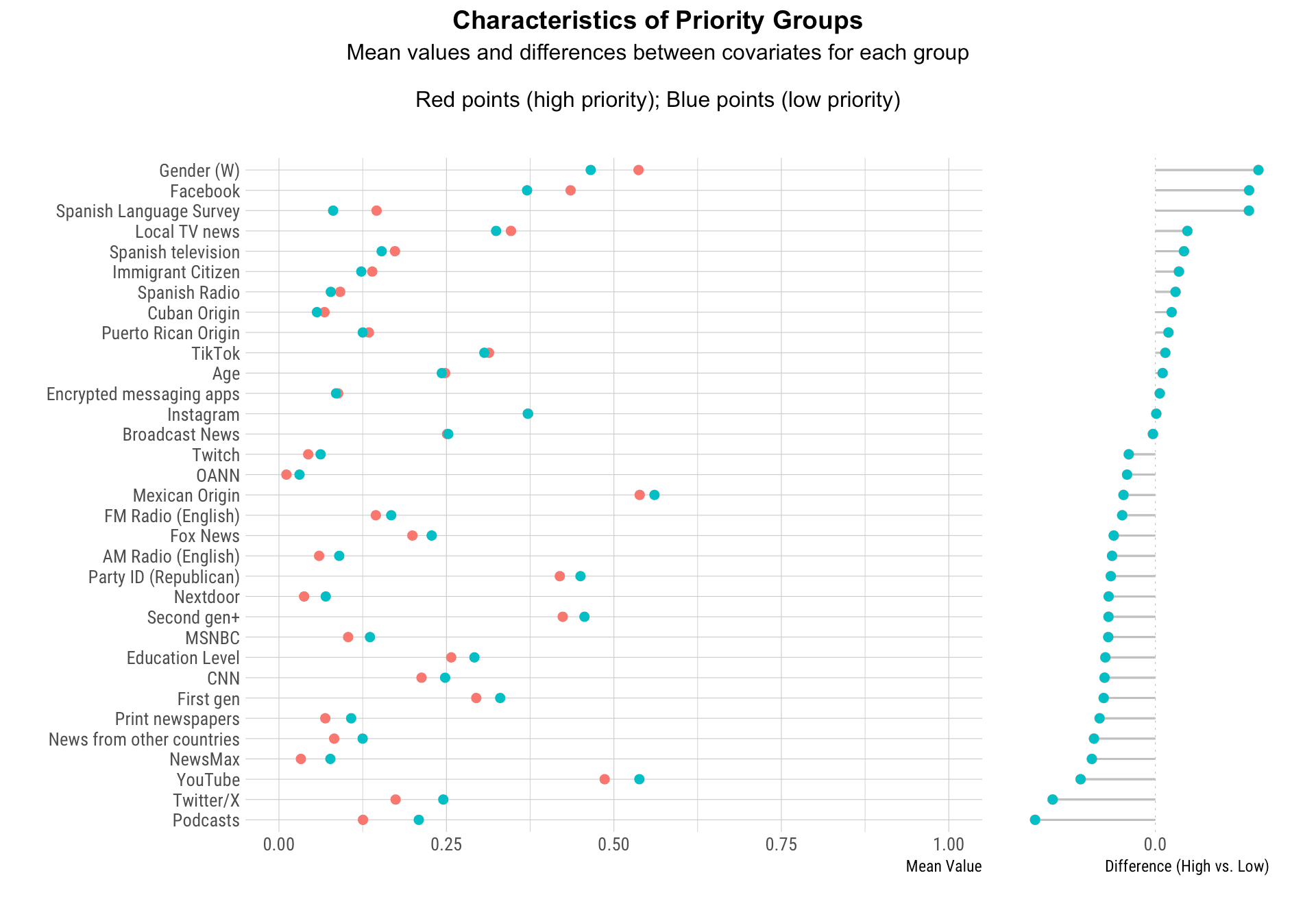

Our data allow us to identify higher-priority Latinos, who are more likely to respond to interventions, and lower-priority Latinos, who may already have more fixed beliefs.

Higher-priority Latinos can be divided into three main groups:

1. Those who are uncertain.

2. Those with low exposure to misinformation but who accept some claims.

3. Those with low exposure who reject some claims.

These subgroups have either not been significantly exposed to misinformation, though this may change as the election season progresses, or they have been exposed but remain uncertain.

In contrast, lower-priority Latinos are either already very able to differentiate between true and false content, or may be believing misinformation at such high rates that they are unlikely to move their thinking much.

Higher-priority Latinos tend to be women, Facebook users, and Spanish-dominant. They also consume slightly more broadcast news and Spanish-language media.

More on Spanish: Spanish-dominant Latinos, compared to their English-dominant counterparts, often show greater uncertainty and are less inclined to dismiss claims they encounter. They also see fewer claims overall. Politically, 41% identify as independents—higher than the 28% among English-dominant Latinos—and only 40% regularly follow politics, compared to 55% of English-dominant Latinos. This limited exposure to both false content and political content in general may hinder their ability to recognize and reject misinformation effectively.

Lower-priority Latinos are more likely to consume podcasts, use Twitter/X and YouTube, engage with ideological media, identify as first-generation Latinos, watch cable news outlets (e.g., CNN, MSNBC, and Fox News), and identify as Republican.

While there are differences between higher and lower-priority groups, focusing efforts on platforms like YouTube could be beneficial, as a majority of Latinos consume media on these platforms. Targeting Mexican Americans, who constitute a significant portion of the Latino community, could also be effective, despite their similar rates of belonging to both higher and lower-priority groups.

To optimize misinformation-reducing efforts, interventions should be tailored to the specific characteristics and media consumption habits of higher-priority Latinos while also considering the broader reach of certain platforms.

Figure 8. Mean estimates for lower- and higher-priority Latinos. In the left panel, blue points represent values for lower-priority Latinos, whereas red points represent values for higher-priority Latinos. In the right panel, mean differences between lower and higher-priority Latinos are shown. As an example, 53% of higher-priority Latinos are women (red point at the top of the figure) whereas 47% of lower-priority identify as such (blue point at the top of the figure). Variables that are more diagnostic of belonging to the higher-priority group are shown at the top.

Trust in Elections and Political Figures

False or misleading claims and narratives about elections, whether they pertain to fraud or “stolen elections,” were among the most widely seen by our sample. 41% of Latinos surveyed who had seen that “Democrats are encouraging undocumented immigrants to vote” believed the claim. 34% who had seen the “Big Lie” believed it.

Though it is unclear whether these claims specifically drive distrust in the political system, they may complement or reinforce these feelings. To that end, we analyzed gaps in trust between Latino Republicans and Democrats. We measured trust in election-related groups such as election officials (e.g., Secretaries of State, poll workers), as well general political actors such as media organizations, political institutions, journalists, political parties, religious leaders, tech companies, social media, scientists, and neighbors.

Figure 9. Mean trust estimates for Latino Republicans and Democrats. Red points represent estimates for Republicans; blue points represent estimates for Democrats.

Latino Republicans and Latino Democrats differ in their levels of trust in elections. Latino Republicans generally are more distrusting of election authorities and actors compared to their Democratic counterparts. These election authorities include poll workers, election administrators, and secretaries of state.

Neither party expresses much trust in the other side to “do the right thing” on election day, highlighting the deep partisan divide in electoral trust. This lack of trust in the opposing party’s actions during elections may contribute to heightened suspicions and doubts about the integrity of the electoral process.

Beyond electoral trust, virtually no group is trusted similarly across partisan lines, with large partisan gaps evident when respondents rate the other side. The only exception to this pattern is trust in neighbors, which could be attributed to factors such as proximity or residential sorting patterns. While partisan gaps are smaller in other cases, such as trust in Congress and social media, these gaps reflect shared ambivalence across partisan subgroups rather than genuine trust. Democrats tend to trust media outlets more than Republicans, with Fox News being the exception to this trend.

Interestingly, scientists emerge as the group that comes closest to being trusted similarly along partisan lines (albeit to different degrees). This bipartisan trust in scientists suggests potential avenues for bridging partisan divides and fostering greater trust in credible information sources.

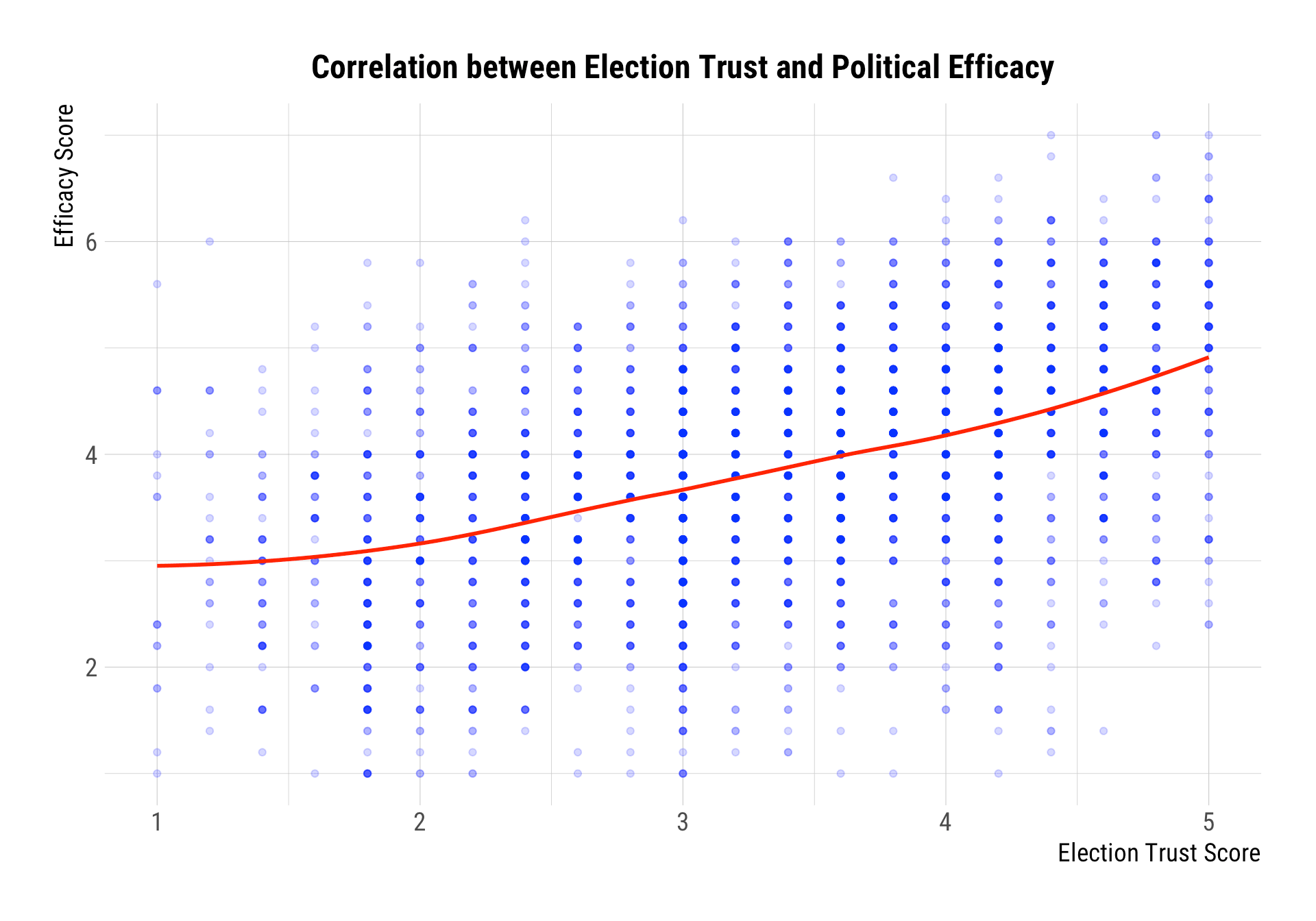

How might trust matter? Beyond making people more receptive to non-credible sources of information, a belief in the narrative that elites are disregarding the will of the people and ignoring election results may have downstream consequences on political engagement. Below, we calculate the mean trust score for the political actors above, constructing a measure of electoral trust, and examine its association with political efficacy.

Political efficacy is seen as one of the building blocks for political action. It is a concept that captures the extent to which people feel like they can have an impact on the political system. In our survey, we used a set of five items featuring questions such as “People like me don’t have any say about what the government does” and “I consider myself well-qualified to participate in politics” to calculate a measure of political efficacy.

Each point represents an individual and their joint scores on the trust and efficacy scales. Among those scoring the lowest on election trust, their predicted efficacy score is 3. This is .84 points below the average efficacy score for the entire sample (3.84). However, we see a steady rise in efficacy as trust increases, with those trusting election officials the most scoring at a 5. This is 1.16 points higher than the average, and a whopping 2 points higher than those on the lower end of the election trust scale.

Though not causal, the analysis suggests trust is worth examining as a factor contributing to beliefs about politicians, susceptibility to misinformation, and broader orientations toward the political system.

Figure 10. Scatter plot of election trust and political efficacy. The different shades of purple represent how frequently those values appear; darker purple dots show more common values. A smooth “loess” line is added to show the overall trend.

We expand upon these analyses by examining correlates of trust, efficacy, and political engagement.

Will My Vote Matter? (Political Efficacy)

Individuals with stronger partisan identities tend to report greater feelings of efficacy - the extent to which their vote will matter. In contrast, older respondents, women, those with more conspiratorial views, and Republicans exhibit lower levels of efficacy.

Trust in Election Authorities

Trust in election authorities is lower among those who identify as Republican, hold conservative views, and score high on conspiratorial orientations. This finding mirrors the results observed for political efficacy. Conversely, political interest and news consumption are associated with greater trust in election authorities.

Confidence that the Vote Will Count

Confidence in one’s own vote being properly counted and self-reported likelihood of voting are also influenced by several factors. Partisan intensity, education, political interest, and news consumption consistently emerge as positive predictors of these attitudes, while holding conspiratorial views and Republican identification is negatively associated with both vote confidence and voting likelihood.

The Connection Between Trust and Turnout

Partisanship and conspiratorial orientations may play a role in shaping sentiments that can undermine support for democratic processes among Latinos. Republican party affiliation, rather than the extremity of partisan views, consistently predicts lower levels of efficacy, trust, and confidence that one’s vote will count.

Interestingly, the analysis reveals a discrepancy between predictors of confidence, trust, and turnout intention.

Despite lower perceptions of efficacy, older individuals are more likely to report a desire to turnout.

Conspiratorial orientations also predict lower efficacy, trust, and confidence that one’s vote will be counted. However, it has a weak association with self-reported turnout intention.

This suggests that for some groups, engagement may not hinge on whether they trust the political process. They may choose to participate in spite of beliefs of “rigged elections” or untrustworthy officials.

Figure 11. Standardized regression coefficients from linear regression models adjusting for all of the listed variables. Each covariate is rescaled to range from zero to one. Four separate models are estimated, regressing each outcome on the set of covariates.

Latinos and AI

Looking toward the future and the potential impact that Generative AI might have on the election, we assessed Latino attitudes toward artificial intelligence (AI) to understand their exposure to and perceptions of these technologies.

Our survey revealed that a majority of respondents had never used AI tools, with only 15% regularly using the most popular Generative AI tool, ChatGPT. Other tools like Bing/Copilot Chat, Midjourney, Dall-E, and Stable Diffusion had even lower regular usage rates.

When it comes to attitudes toward AI, respondents were largely ambivalent. Nearly half (47%) viewed AI as “neither positive nor negative,” while the remaining responses were evenly split between seeing AI as positive (27%) or negative (27%). Despite this ambivalence, there was a strong consensus on the need for regulation, with many expressing concerns that AI technologies could lead to job displacement.

While respondents acknowledged the potential benefits of AI in areas such as productivity and medical advancements, their overall sentiment remained cautious. The majority of respondents scored around the midpoint on scales measuring positive aspects, reflecting a lack of strong opinions in either direction. This ambivalence indicates that while the potential of AI is recognized, it is tempered by concerns about its socioeconomic impacts.

Despite some pessimism about AI’s broader societal impacts, respondents were more optimistic about its political implications. Only 28% believed AI could be a “game changer” in the 2024 election. The majority viewed AI’s political impact as either marginal or non-existent, with 41% agreeing that “The 2024 election will look just like every other election,” compared to 31% who saw AI playing a minor role through chatbots and personalized information.

Interestingly, positivity toward AI was influenced by exposure and interactions with the technology. Users of Generative AI tools like ChatGPT, Dall-E, and Midjourney were generally more positive about AI’s potential benefits, particularly in scientific discovery and productivity. However, even these users supported regulation and were concerned about job displacement, showing that familiarity with AI does not necessarily alleviate all concerns.

Overall, our findings suggest that AI is still an emerging technology for most Latinos, and its societal impact is not yet fully realized. While there is general ambivalence toward AI, concerns about job loss and the need for regulation are prevalent. Politically, AI’s influence is not seen as significant by many respondents, indicating that its role in shaping American politics and society may not yet be fully appreciated.

Moreover, a lack of exposure to AI may make it difficult for Latinos to fend off harmful content generated by these technologies. To address this, AI literacy training, akin to the adoption of digital literacy programs, could be crucial. Such training would equip individuals with the skills to critically evaluate AI-generated content, understand the implications of AI in various sectors, and effectively navigate the digital landscape.

As technology continues to evolve, fostering resilience through education and encouraging companies developing these technologies, both generative and non-generative, to be more mindful of societal impacts becomes increasingly important.

Fostering Resilience

Findings from our poll confirm crucial findings that we observed in 2022. Latinos are not falling for misinformation on a large scale. Despite exposure to false narratives and specific claims about elections and science, a majority of Latinos navigate their information environments with a level of skepticism and discernment. Moreover, we find that Latinos are just as capable as the general population in differentiating between true and misleading headlines.

These findings, however, do not suggest that there is no cause for concern. While Latinos see a lot of specific false claims online and few accept them, there are broader narratives about politics that seem to resonate with our sample. Many of these narratives imply that shadowy elites are determining outcomes behind the scenes, and large chunks of our sample accept them. Beliefs in narratives are important because they might increase the adoption of false claims. For instance, those who believe elections are compromised because “Democrats have won elections by resorting to fraud and electoral manipulation” or “Russia is controlling American politics by undermining our elections and causing rifts between Americans” may be willing to accept and spread falsehoods about rigged elections.

Beyond serving as schemas that enable false beliefs, narratives are important to study because they transcend elections. Practitioners should not lose sight of this when countering misinformation. Though it is helpful to target false claims as they spread online with interventions such as fact-checking, it is worth remembering that claims are disconnected from the narratives they reinforce. A multi-pronged strategy that tackles discrete claims while paying attention to the acceptance of broader narratives about politics may be especially productive.

The adoption of anti-elite narratives also speaks to a crisis of trust within the community. Latino Democrats and Republicans are largely split on how they feel about election officials such as Secretaries of State, poll workers, and election administrators, with Latino Republicans expressing ambivalence. Partisans on both sides distrust each other, and there is little consensus between both groups on political actors that are trustworthy. This may help explain widening gaps between both groups over basic facts, as trustworthy sources that speak to both sides of the aisle become increasingly scarce.

As we approach the 2024 election, we are sure to see a swirl of misinformation reaching Latinos. We should not expect Latinos to accept much of what they see. But, we should keep a watchful eye on general feelings of skepticism and uncertainty that may prevail, as general distrust of both misleading and credible sources of information can also harm political participation and support for democracy.

As our work has shown, promising tools like fact-checking, accuracy prompts, and inoculation are out there, but more is needed to tailor these tools to our community. This year, DDIA will be carrying out a randomized controlled trial studying the impact of culturally-tailored inoculation methods and producing a guidebook for practitioners interested in implementing these approaches. By leveraging trusted messengers, educational campaigns, and culturally tailored resources, we can enhance the resilience of the Latino community against misinformation, ensuring that they remain well-informed and engaged in the democratic process.

Access the Report PDF:

DownloadAccess the Deck PDF:

Download