Also read:

Part 1 of 3: In and Out of the Rabbit Hole: Exploring Misinformation Adoption among Subgroups of Latinos in the United States

Part 3 of 3: Seeking Antidotes to Misinformation: An Analysis of Effective Counter-Strategies among U.S. Latinos

It goes without saying that exposure (seeing) and acceptance (believing) are two crucial elements of misinformation adoption. In the first of our three-part series of analyses of a 2022 misinformation poll conducted by Equis, we reaffirmed Equis’ finding that a majority of Latinos surveyed were not outright believing misinformation, whether because they were not familiar with or had not come across the false claims (lack of exposure), because they were uncertain whether the claims were true or false, or because they outright recognized the claims as false and rejected them.

This majority, Level 1 Latinos as we called them, did not report believing any of the false narratives Equis tested. They differed from counterparts who had either adopted one false claim (Level 2) or two or more false claims (Level 3). We also noted that the Latinos who both saw and believed misinformation more often, the Level 3 Latinos, tended to be more conspiratorial, more partisan, and more politically engaged.

Though this is a useful first step in understanding Latino communities’ familiarity and belief in misinformation, drilling further into the subgroup categories can inform how we address the issue. For example, some U.S. Latinos may be exposed to a lot of misinformation and reject it all, exhibiting high levels of discernment. These individuals may be lower priority for interventions but could make for trusted messengers. In contrast, Latinos who are exposed to a lot of misinformation and remain uncertain may require more attention, as targeted campaigns or social pressure could tip them towards acceptance.

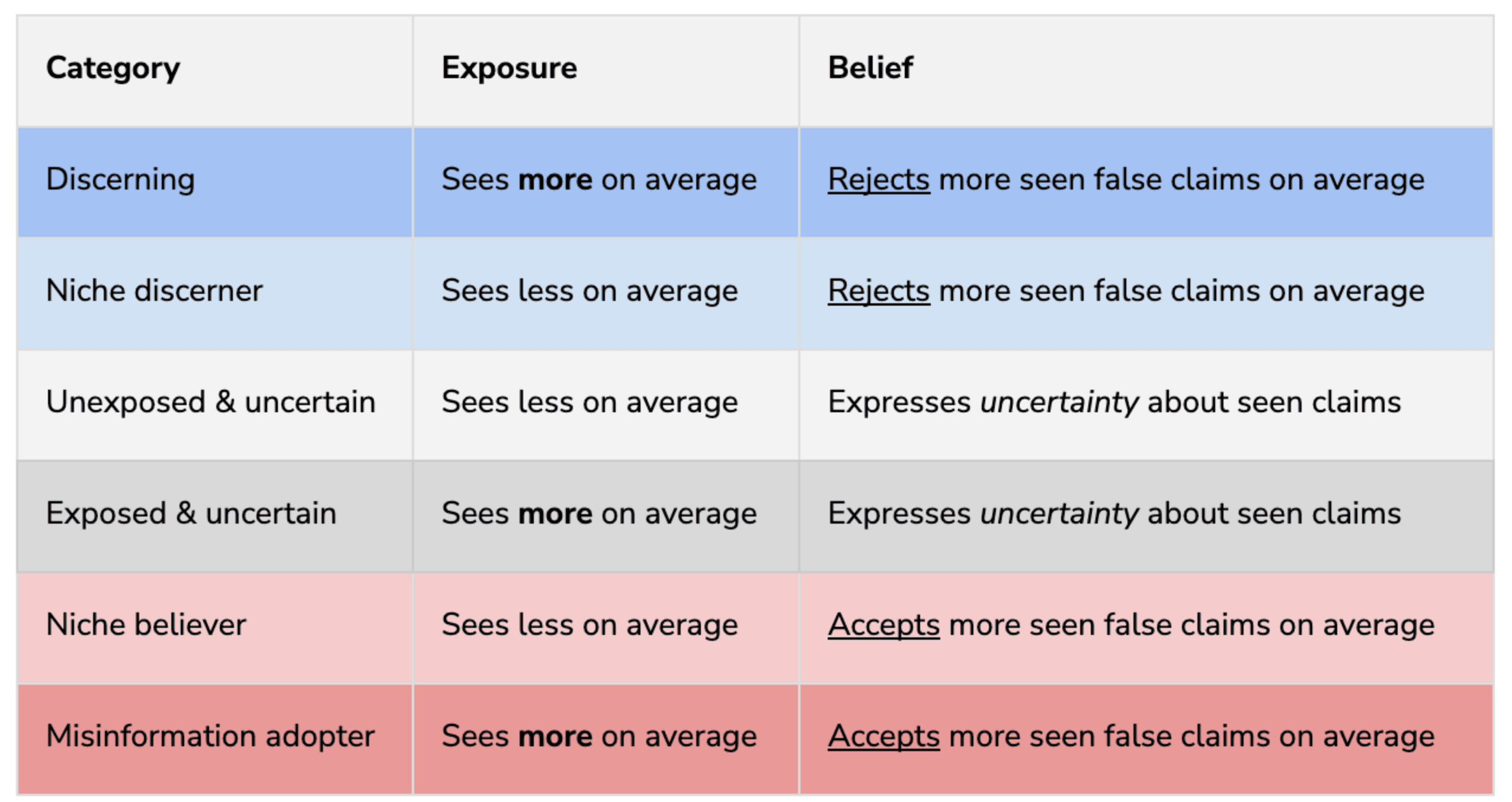

In this post, the Digital Democracy Institute of the Americas (DDIA) develops a typology that takes exposure, uncertainty, and the direction of beliefs (i.e., rejecting or accepting false narratives) into account. Specifically, we further segment the sample into six categories based on exposure (below-average exposure, above-average exposure) and belief (rejecting more seen claims, uncertainty, and accepting more seen claims) to identify different priority groups:

Table 1. Our six-category typology of misinformation adoption. We consider three elements of misinformation adoption: uncertainty, exposure, and belief adoption.

As in the previous post, we describe the prevalence of each category of respondent in the population. We also analyze these groups using a set of political, psychological, and demographic variables to assess what distinguishes Latinos who have adopted misinformation from those who haven't.

Our takeaways:

Consistent with our previous analysis, those who confidently accept false narratives are a minority of the population, but this does not mean that Latinos are not at risk for misinformation. Many express uncertainty about false narratives, and targeted campaigns could move some toward acceptance.

Misinformation adopters are more conspiratorial and more likely to consume partisan media on both sides; niche believers have similar demographic characteristics, but tend to be less politically engaged.

Discerning Latinos tend to be wealthier, less conspiratorial, and are less likely to consume partisan media; niche discerners who see less misinformation but also reject false claims also tend to mirror their more exposed counterparts, but they are slightly less engaged.

In contrast to media narratives painting Latinos as easily accepting falsehoods, the good news is that the sample's largest group – “unexposed & uncertain” – consists of Latinos who are exposed to little misinformation and are uncertain about it (28%). The second largest group is "discerning" Latinos who have seen more misinformation on average and reject what they have seen (23%), followed by “misinformation adopters” who see a lot of misinformation and accept what they see (15%).

The remaining categories include the 14% who see less misinformation and reject seen claims (niche discerners), the 10% who see less misinformation but accept the claims they have seen (niche believers), and finally, the 10% of the sample that is exposed to a lot of misinformation but remains uncertain about it (exposed & uncertain).

Figure 1. Distribution of misinformation types within the sample.

Latinos and Misinformation: Understanding Subgroups

With the richer typology in hand, we profile the different categories in Figure 1. First, we begin with those who have adopted misinformation, before turning our attention to discerning and uncertain subgroups.

Starting with those who believe misinformation, 60% of those who are misinformation adopters – seeing and believing more false claims on average – score at the upper end of conspiratorial thinking. 47% and 53% of misinformation adopters score at the upper end of liberal and conservative media consumption, respectively, which also further distinguishes this group as one that consumes partisan media.

For most of the remaining demographic, political, and psychological variables, misinformation adopters look like niche believers, defined as those who see less misinformation on average and accept more seen false claims on average, with a few exceptions. Niche believers tend to be older, lower income, less politically interested, and more likely to speak Spanish. Overall, these may be people who have heard a stray piece of misinformation from a friend or family member, but are not plugged into media channels or networks where false narratives are propagated.

Turning back to the distinctions between Level 2 and 3 Latinos from our first post, this group is reminiscent of Level 2 Latinos, who have started leaning into some misinformation but have not adopted the larger constellation of falsehoods.

Figure 1. Heatmap depicting conditional averages for each subgroup. Darker shades of red indicate that a greater share of the subgroup scores higher on the variable.

On the opposite end of the spectrum are discerning Latinos, who see a lot of misinformation and reject it outright. Those in the discerning category tend to be older, more liberal, less likely to identify as Evangelical, wealthier, more educated, and less likely to follow partisan media when compared to misinformation adopters. They are also similar to niche discerners across a variety of demographics.

Partisan media consumption patterns, higher income, first-generation status, political interest, and liberal ideology tend to be higher for the discerning relative to “niche discerners”, whereas Spanish media consumption and Spanish dominance tends to be lower. These are older, more liberal, wealthier, and politically engaged Latinos who may consider themselves “political junkies.”

Focusing now on the uncertain, both the exposed and unexposed tend to consume less partisan media compared to the other groups. They also tend to have a lower rate of college education and possess weaker partisan identities.

Compared to those who accept some or a lot of misinformation, the “exposed & uncertain” are close to niche believers on variables such as conspiratorial thinking, partisan media consumption, and political interest.

The “unexposed & uncertain” closely mirror niche discerners, with some major exceptions: they are less wealthy, less politically interested, more likely to speak Spanish, less likely to identify as male, and skew younger. This group can be thought of as a somewhat less engaged segment, potentially less influenced by the mainstream political discourse and more reliant on personal networks.

Some of the uncertainty from this group may come from less exposure to politics, but also the lack of a firm grounding in a specific party or ideology. As we described in our first post, seeing more misinformation and possessing identities or affiliations that increase the stakes for believing false claims are two important risk factors for adopting misinformation.

Tailoring Misinformation Counter-measures

Separating the Latino community into subgroups based on exposure and belief can be helpful when considering how to best target counter-misinformation interventions. Rather than relying on a one-size-fits-all solution, scholars and practitioners should consider baseline needs, competencies, and information environments when deciding where and how to spend resources in combating the problem.

Turning to the six categories, we can make following recommendations, which we will go deeper into in the last of this three-part series:

Discerning – These are Latinos who are exposed to a lot of misinformation and actively reject it. They’re almost as politically engaged as adopters, but do not spend as much time consuming partisan sources. Strategies like inoculation could be used to bolster defenses. They might also serve a role within their communities as trusted messengers who help others navigate information environments.

Niche Discerners – These individuals are exposed to less misinformation and also actively reject it. If they are flooded with misinformation during the general election that targets a variety of beliefs or values, this can change. Bolstering defenses with inoculation or digital literacy may help. Debunking popular claims might also be useful for this group.

Exposed and Uncertain – This group is seeing a lot of misinformation and still remains on the fence, or uncertain. Digital literacy, proactive messaging, reinforcing critical thinking, and soundly rejecting seen claims via fact-checking should be the focus. With greater clarity about the validity of claims circulating during election season, this group may be less likely to tip over into the higher adoption categories.

Unexposed and Uncertain – This group has limited exposure to misinformation and is uncertain about what they do see. Community-based interventions that educate on how to critically assess information could be effective as a way to get ahead of potential exposure to misinformation they may have in the future.

Niche Believers – Niche believers see less misinformation and tend to believe it. Given that their profile is very similar to misinformation adopters, focus on debunking the specific claims they are exposed to. Introduce critical thinking exercises and provide reliable information in easily digestible formats, possibly in Spanish.

Misinformation Adopters – Given their high exposure and acceptance rate of misinformation, coupled with a strong inclination towards conspiratorial thinking, the challenge is to get them out of the rabbit role. Introducing depolarization techniques that encourage more realistic views of political opponents, including interventions that challenge preexisting beliefs, debunking, and credible messages from aligned sources may be essential here.

Our research presents a nuanced framework for assessing how misinformation circulates among Latinos. The typology developed here allows for targeted interventions that consider not only the level of exposure to misinformation but also the acceptance or rejection of it. This multidimensional approach offers more precise avenues for intervention, moving beyond generalized strategies that may not be effective for all subgroups.

With election season approaching, scholars and practitioners should be mindful of the delicate interplay between exposure, uncertainty, and belief. Though we find that few Latinos are “misinformation adopters” who see and believe a lot of false claims, our findings are based on data from January and February of 2022.

Some of the unexposed may be bombarded with false claims as we approach the fall of 2024. Equipping this group with the tools to discern false from true narratives, as well as the misleading frames in between, will be crucial. Similarly, misinformation adopters, who are already entrenched in false beliefs, may require specialized interventions, potentially involving family or community leaders who can break through the barriers of partisan or conspiratorial thinking. By applying this nuanced typology, stakeholders can engage in more targeted and effective campaigns to mitigate the spread and impact of misinformation.