Access the Report PDF:

DownloadEXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Every year, cancer claims millions of lives globally. Per the World Health Organization, by the year 2050, 35 million new cancer cases are predicted worldwide, a 77% increase from 2022.

In the United States alone, where the Digital Democracy Institute of the Americas (DDIA) is headquartered, the National Cancer Institute estimates that yet this year, over 2 million new cases of cancer will be diagnosed and over 600,000 people will die (said another way, more people will die of cancer in 2025 than currently reside in the cities of Milwaukee, WI, or Baltimore, MD).

Despite advances in early detection and treatment of many cancers, the reality is that in a polluted online environment – where on average people spend at least 2.5 hours every day globally – individuals are frequently exposed to a host of damaging information about cancer that can have very real implications for their health.

To fill gaps in understanding of how Spanish-speaking Latinos and Latin Americans are engaging with potentially harmful cancer-related information, the Digital Democracy Institute of the Americas (DDIA) analyzed more than 27,000 posts from the first quarter of 2025 across four major social media platforms.

At a time when people regularly rely on platforms like X, TikTok, Facebook, and Instagram for news and information about topics that deeply impact their lives, this analysis offers:

a look at how problematic cancer-related narratives are spreading,

a breakdown of the common tactics being used to help content resonate,

a glimpse at how content commonly shows up across the four platforms,

and recommendations on what can be done to assure communities have access to life-saving information across languages and the trusted connections needed to approach information from a frame of credibility.

TAKEAWAYS

Key Trends

Three buckets of harmful content draw high levels of engagement on social media. These include information about alternative or miracle cures, false preventative measures, and questionable causes of cancer.

Discussions about cancer are often driven by emotion, pseudo-science, and fake experts. Harmful cancer narratives in Spanish-language social media are notably exacerbated by fear, frustration, and distrust in elites and institutions.

Misinformation about cancer exploits emotions and gaps in scientific knowledge to make complex issues feel simple and urgent. Falsehoods in Spanish travel fast and appear in unique ways across platforms.

Narratives suggesting cancer is easily avoidable can stigmatize patients, implying they are at fault for the illness.

The debate around vaping vs. smoking – specifically about which is the healthier option – remains unresolved online, giving space for misleading, and often industry-backed, narratives to spread.

Many viral falsehoods are rooted in “global control” beliefs connected to people and institutions in positions of power. These include:

Elites hiding a cure; and

Western powers manipulating health systems to maintain control over populations

Common Tactics of Manipulation

Misinformation consistently harnesses tactics of manipulation to reach virality. The most commonly used tactics in cancer-related conversations seem to be:

Emotional language: Posts leverage personal stories, images of patients, and religious themes to create empathy or urgency. Fear-based messaging promotes distrust in institutions and encourages audiences to reject traditional medicine in favor of unproven alternatives. Fake donation appeals often exploit personal stories to solicit money under false pretenses.

Pseudo-scientific language and fake experts: Posts mimic academic tones, cite fake or distorted research, and use complex jargon to appear credible. Messaging creates the illusion of authority while spreading “hidden truths.”

These tactics are effective because they tap into people’s desire for control, hope, and simple answers in the face of a frightening and complex disease.

How Cancer Information Appears Across Platforms

X: Dominated by politicized content, posts combine false or misleading information with accusations against governments and public health systems.

TikTok: Serves as hub for emotional storytelling, where personal cancer journeys (real or fabricated) blur the lines between support and manipulation.

Facebook and Instagram: Posts are highly visual, simple, and shareable. Misinformative posts rely on infographics and minimal text to spread false cures and unproven advice about cancer prevention

Recommendations For Cleaning Up the Information Ecosystems Where Harmful Cancer Discussions Spread

FOR HEALTH INSTITUTIONS: Health institutions must go beyond fact-checking specific false or misleading claims about cancer, keeping in mind the importance of addressing the emotional and political roots of cancer misinformation with empathetic, culturally relevant content. Prebunking tactics can help inoculate audiences against common manipulation techniques, but broader investments should be made in proactive, accessible, and available communication and connection with trusted scientists and doctors at the local level.

FOR SOCIAL MEDIA PLATFORMS: Social media platforms already ban groups that promote fake cancer treatments and suppress posts that promote false health claims, but each platform must do more to tailor strategies to the unique ways this content can show up on the platform, and boost visibility of credible Spanish-language content.

FOR CIVIL SOCIETY: NGOs and cancer advocacy groups must monitor viral moments (passings of celebrities, for example), work with trusted doctors to produce explainers and tell positive stories, and produce rapid-response content that speaks to audience emotions.

FOR GOVERNMENTS: Governments should recognize cancer misinformation as both a public health and digital resilience issue, supporting media literacy and cross-border collaboration. Some institutions already offer hotlines for questions, such as the National Cancer Institute’s Cancer Information Service, but more must be done to get this information out of government websites and into the hands of online users where they get their information.

HARMFUL NARRATIVES ABOUT CANCER ON SOCIAL MEDIA

Prevalent Buckets of Information

Three buckets of harmful content draw wide Spanish-language engagement within the cancer information ecosystem on social media: 1) alternative or miracle cures, 2) false preventative measures, and 3) questionable causes of cancer.

Alternative or Miracle Cures

Two types of unverified “alternative” or repurposed treatments to cancer – often presented as miracle cures – appear often amid larger conversations about cancer: medical and natural treatments.

On the medical treatments side, the promotion of drugs like ivermectin and fenbendazole as cures for cancer can be seen widely online, often pushed by known conspiracy theorists and actors with large followings, like Mel Gibson.

On the “natural” treatments side, posts (across text, images, and videos) push alternatives to chemotherapy or other proven interventions. These include alkaline water (a mix of warm water, lemon, and baking soda) and natural ingredients like apricot seeds, turmeric, honey, oranges, and herbs. On Facebook alone, content about alkaline water garnered over 400,000 interactions during the study period.

Claims that advocate for false or alternative treatments often harness small grains of truth to push larger points about supposed cures.

In the case of medical alternatives such as ivermectin and fenbendazole, spreaders online harness the point that anti-parasitic drugs have shown minor effects in the lab and largely ignore the fact that cancer is not parasitic and that neither drug has been tested in humans. In these instances, those pushing such interventions ignore the lack of robust data scientists require to make clear treatment recommendations.

In the case of natural treatments, social media users seemingly approach the conversation from the point of view that conventional treatments like chemotherapy are “overly aggressive” and reduce a patient’s “quality of life.”

Underpinning these types of conversations is a broader distrust of elites and institutions, including suggestions that pharmaceutical companies (and sometimes governments) are hiding natural cures for profit. This type of thinking overlaps with broader anti-establishment and global control narratives frequently seen in the world of political misinformation.

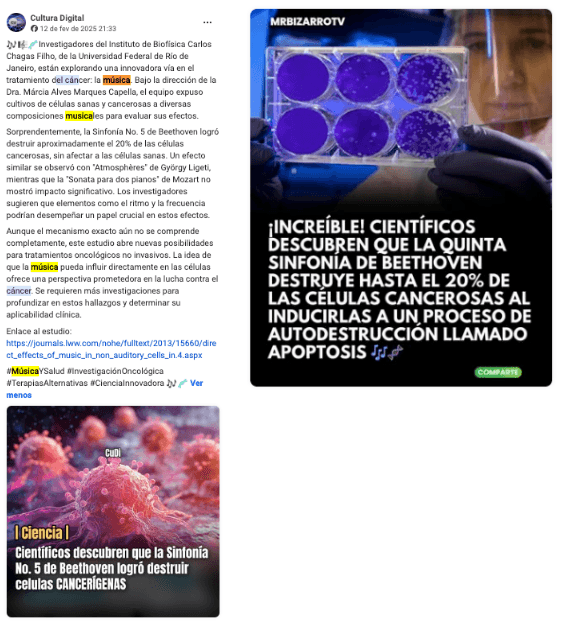

Conversations about miracle cures span languages and cross borders. One especially unique example that spanned borders was the viral claim that Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony could cure breast cancer. This idea was loosely based on a 2011 experiment in Brazil where breast cancer cells in petri dishes were exposed to classical music – including works by Beethoven, Mozart, and Ligeti. The study showed some increased cell death with Beethoven and Ligeti, but it did not involve human testing, lacked scientific rigor, and was abandoned due to lack of funding. Despite this, the story resurfaced in 2025 and became one of the most shared cancer-related posts in Spanish during our analysis.

False Preventative Measures

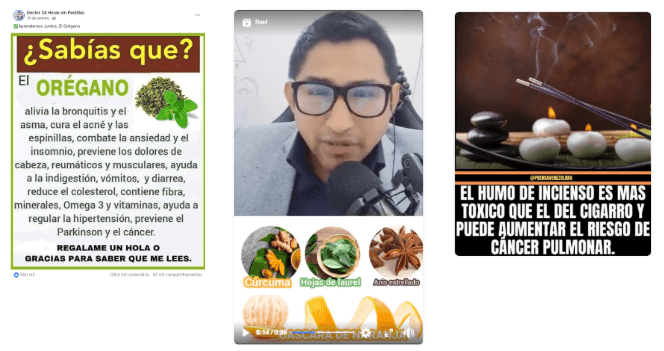

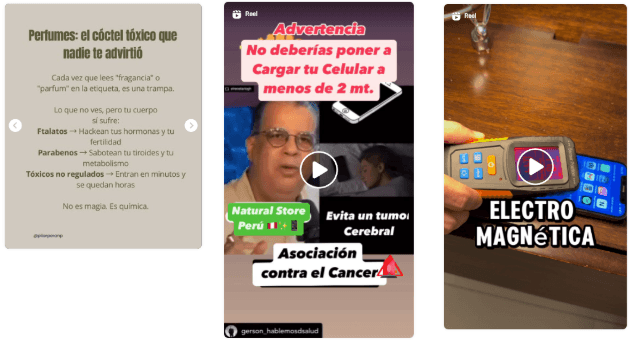

The prevention of cancer, often discussed alongside miracle cures, is another prominent topic of conversation on social media. Throughout early 2025, hundreds of Spanish-language posts recommended eating orange peels or oregano to ward off cancer, while warning against everyday items like incense, perfumes, mobile phones, and 5G networks. These claims – often rooted in the belief that nature alone can protect us – were rarely challenged by factual content or corrections.

The scale of engagement was staggering:

Posts linking electromagnetic radiation to cancer drew 27.5 million interactions on Instagram alone.

Claims connecting mobile phones to brain cancer totaled 6.7 million interactions.

Allegations that perfumes contain carcinogenic chemicals reached 8.7 million interactions.

Our researchers also found that anti-vaccine narratives remain deeply entrenched in these discussions. While some pages and social media accounts actively promote HPV vaccination and express interest in potential cancer vaccines (particularly one from Russia targeting lung cancer), other posts wrongly link mRNA vaccines to cancer. They mention unproven theories and sow doubt by calling these vaccines “experimental.”

This type of content fuels fear and distrust toward vaccines that are generally safe and scientifically supported. These posts appear to be part of a broader, coordinated effort to discredit public health messages and promote hostility toward “big pharma.”

Questionable Causes

Finally, many misleading narratives focus on oversimplifying the causes of cancer (excessive use of 5G, for example), often pushing the idea that small lifestyle tweaks (like the ones described in the “preventative measures” section, above) can fully prevent the disease.

These claims offer a dangerous illusion of control, suggesting that avoiding certain products or behaviors (regardless of scientific evidence) can eliminate cancer risk. This framing not only promotes countless “miracle” substitutes (and opens room for scammers) but also reinforces a damaging belief: that people who develop cancer simply weren’t careful enough.

This type of messaging can stigmatize patients, feeding guilt and shame while distorting public understanding of a complex disease.

One particularly heated topic in early 2025 was the debate around vaping versus smoking. Spanish-speaking users across platforms fiercely discussed whether e-cigarettes were safer than traditional tobacco products. In many cases, the content echoed marketing narratives pushed by the vaping industry, portraying vaping as a risk-free alternative.

Posts warning about vaping’s dangers generated 4.8 million interactions on Instagram.

Those promoting vaping as a safe choice gathered over 3.1 million engagements.

Motives Expressed by Users as Reasons to “Believe” Misinformation

Fear, frustration, and deep distrust are catalysts for the spread of cancer misinformation on social media. In the analysis of more than 27,000 social media posts, DDIA found that many Spanish-speaking users engaging with cancer-related falsehoods express suspicion far more often than they express confusion due to a lack of information.

Many believe that elites are hiding a cure, that pharmaceutical companies care more about profits than patients and so intentionally keep things from society, and that Western powers might be using health to maintain global control. These conspiracy-laden narratives gain traction because they offer simple, emotionally satisfying answers to a disease that feels complex and terrifying.

Three of the most common meta-narratives, or stories, identified include the following::

“Elites are hiding the cure.”

This belief assumes that powerful actors are deliberately keeping the public in the dark, suppressing simple, natural cures to preserve control over society. Under this narrative, mainstream medicine is not only ineffective, it is also part of a global system designed to keep people dependent and powerless. Posts promoting this idea often reject chemotherapy or radiation, claiming they are “tools of control,” and frame natural remedies as secrets worth fighting for.

“Pharmaceutical companies only care about profit.”

Extreme distrust of the pharmaceutical industry is another major driver of misinformation regarding natural cures to cancer. Many viral posts in Spanish argue that drug companies suppress low-cost alternatives (like turmeric, alkaline water, or apricot seeds) because they can’t be patented. As a result, some users reject conventional treatments, seeing them as part of a profit-driven machine. Sharing misinformation in this context feels like an act of resistance, a way to protect loved ones from being exploited.

“Western powers are using health to stay in control.”

Some cancer-related falsehoods go beyond health and dive straight into geopolitical messaging. Across all platforms, cancer is being used as a tool to sow political distrust and stoke anti-Western sentiment, including among Spanish-speaking communities.

One of the most striking examples is the promotion of a Russian-developed mRNA cancer vaccine, often framed as a groundbreaking medical breakthrough that Western countries are supposedly ignoring or suppressing. These narratives suggest a coordinated effort by the U.S. and its allies to maintain control over global health systems by discrediting non-Western solutions. They tap into national pride, presenting Russia as a savior of the people and the West as an obstacle to progress.

This content is especially potent in regions like Latin America, where historic skepticism toward Western influence remains strong. DDIA detected repeated claims stemming from Spain and Mexico claiming that local governments are hiding cures, underfunding treatment, or colluding with pharmaceutical giants to keep citizens sick. After the government of Mexico faced heavy criticism for not following the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and not banning Red Dye No. 3, a synthetic coloring used to make foods and drinks bright red, discussions about this issue generated around 4 million engagements on Instagram during the study period.

TECHNIQUES USED TO MANIPULATE USERS

Misleading styles of argumentation or persuasion are often used to influence social media discussions. Understanding how these messages are crafted is the first step toward becoming more resistant to manipulation, and is also a tool for creating smarter, more effective responses to online harms.

With the help of AI tools (ChatGPT and DeepSeek), DDIA analyzed thousands of posts collected in the first quarter of 2025 and identified two dominant manipulation techniques used in the spread of cancer-related harmful discussions online: emotional language and pseudo-scientific language.

Emotional Language

Many misleading posts about cancer lean heavily on emotionally evocative language, images, and stories, especially photos of patients (sometimes with family members, children, or in hospital settings) to create instant connection and sympathy on social media.

The emotional appeal is often exploited in false donation campaigns, where fabricated patient stories are used to solicit money. These scams not only spread misinformation but also erode public trust in legitimate fundraising efforts.

Fear-mongering is frequently used in the emotional manipulation playbook. Posts using this emotional language frame frequently tap into distrust of governments and corporations, including larger theories around elites and institutions controlling society and the world. These messages commonly urge users to distrust doctors, scientists, and institutions like the World Health Organization, framing them as complicit in a system that keeps the truth out of reach. By presenting traditional medicine as part of the problem, these narratives push audiences toward fringe ideas, alternative treatments, and isolated online communities.

Religious content that links cancer to faith or divine intervention is also common in this universe, reinforcing the idea that spiritual belief can heal where medicine has failed.

Pseudo-Scientific Language

To appear credible, many cancer-related falsehoods are wrapped in the language of science, but lack the substance. Posts often misrepresent real research, cite dubious or non-existent “experts,” and use highly technical or obscure terms to create an illusion of authority.

This tactic makes it harder for everyday users to distinguish between legitimate health guidance and misinformation. By mimicking the style of scientific communication, these posts deceive audiences into believing they’ve uncovered a “hidden truth” that medical professionals won’t tell them.

Note: Google Jigsaw’s research on prebunking and inoculation theory, in partnership with the University of Cambridge, lays out the full scope of manipulation tactics used to illicitly influence people online. The tactics identified by DDIA in Spanish-language cancer-related posts (such as emotional manipulation and pseudo-scientific framing) are extensively covered in Google’s findings, offering a valuable foundation for those looking to counter cancer misinformation with clarity and impact.

PLATFORM-SPECIFIC TRENDS

Cancer-related discussions about miracle cures, false preventative measures, and questionable causes are seen across social media platforms. However, the way in which discussions are presented can show up in unique ways within each environment.

X: Where Health Meets Politics

On X, Spanish-language cancer discussions often blur the line between the medical and the political. Many posts reviewed by DDIA combined health claims with accusations against governments, alleging poor cancer treatment policies, lack of funding, or corruption. The common thread is (again) distrust – not just in treatments, but in entire health systems and regulatory bodies. On X, cancer is in many ways a gateway to promoting skepticism toward public institutions and official medical guidance.

TikTok: Emotional Storytelling at Its Peak

Harmful or problematic TikTok posts about cancer stand out for their use of deeply emotional, personal videos (some uplifting, others heartbreaking). These stories often feature individuals claiming to have found miracle cures or alternative lifestyles that “beat” cancer, but offer few pathways for verifying what’s real and what’s fabricated. The platform’s short-form video format makes it easy for misleading narratives to feel authentic, blurring the lines between genuine experience and false stories.

Facebook and Instagram: Visual Simplicity, High Impact

On Facebook and Instagram, cancer-related posts tend to be highly visual and easy to digest. Many harness simple graphics, infographics, and minimal text to push claims about fake cures or preventative measures. These posts are designed to be scroll-stopping and self-explanatory, relying on strong imagery rather than detailed arguments. The simplicity makes posts very shareable.

THE ROLE OF CELEBRITIES IN THE SPREAD OF CANCER MISINFORMATION

Social media has fundamentally transformed how people perceive, interact with and engage with celebrities and their personal stories on social media. Not surprisingly, celebrities have become both the drivers of conversations online and the center-piece of social media discussions. The dramatic nature of tragedy, disease and celebrity come together in cancer discussions online.

From the outset of DDIA data collection that took place between January and April, it became clear that Spanish-speaking social media users highly engage with celebrity cancer stories.

Figures like King Charles and Princess Kate Middleton figured prominently into conversations tracked in the first quarter of 2025, with Spanish-language posts about their diagnoses and treatments going viral across platforms. These publications were often charged with emotions. Calls for prayers were common, as were conspiracy theories questioning the truth or motives behind official updates.

Even after the tracking period, as the preparation of this report was being finalized, former U.S. President Joe Biden publicly announced a cancer diagnosis, and former Uruguayan president José “Pepe” Mujica passed away after his own battle with cancer. Both events (registered in mid-May) became central topics in Spanish-language media and online conversations in less than 24 hours – triggering a surge of emotional responses and misinformation.

Mujica’s death – on May 13, 2025 – illustrated how narratives around his cancer and his death evolved differently depending on the platform. While most social media posts praised the Uruguayan leader and mourned his passing, emphasizing how complicated it is to deal with cancer, messages shared on Telegram public channels told a different story. There, our monitoring captured a wave of hostile publications, attacking Mujica and politicizing his illness in ways that didn’t appear in mainstream public discourse. We wrote an entire edition of our weekly newsletter – REDESCover – about this.

Biden’s announcement – on May 16, 2025 – sparked its own wave of skepticism and distrust. False claims began to circulate, alleging that his cancer had been hidden for years, ignoring official medical reports (including a February 2024 assessment) that found him in good health with no evidence of ongoing cancer or other serious conditions. Once more, the idea that the powerful hide the truth about this disease was present – and widely shared.

Overall, in Spanish-language social media, celebrity cancer stories seem to function as more than just news – many stories become emotional anchors, political battlegrounds, and cultural reference points. When a public figure shares their cancer journey, it opens the door for complex conversations about health, inequality, truth, and trust. All of this unfolds extremely quickly on algorithm-driven platforms that often reward engagement, not always accuracy.

RECOMMENDATIONS

With the intent to cultivate a healthier online environment for Latinos and Latin Americans—an objective central to the mission of DDIA—the below recommendations lay out opportunities for stakeholders confronting the challenges posed by cancer-related online harms and misinformation within Spanish-speaking digital spaces.

For more recommendations, DDIA also recommends reading the National Academies of Science report on Understanding and Addressing Misinformation About Science.

For Health Communicators, Journalists, and Public Health Institutions

Address the emotion, not only the facts: Cancer misinformation thrives on empathy, fear, distrust, and other emotions. Communications should evaluate the importance of acknowledging patients’ anxieties and the appeal of simple “miracle” cures, while offering empathetic, culturally relevant, and scientifically sound alternatives.

Invest in prebunking strategies: Harness inoculation theory to expose and explain to audiences what they may encounter in searching online, including common manipulation tactics like pseudo-scientific jargon as well as commonly debunked cures. Health communicators should take into consideration that many people are more distrusting or uncertain than they are gullible. Do not frame information in a way that makes people feel dumb or defensive.

Ensure Spanish-language content and resources about cancer treatments and causes are easily available and accessible online: Institutions should produce timely, platform-specific, and linguistically tailored resources in accessible ways. “Showing and telling,” including offering and breaking down evidence of what is being said, can be more effective than simply stating something outright.

For Social Media Platforms

Invest further in understanding how unique platform features connect with or exacerbate cancer-related information spread. DDIA analysis shows that emotional videos dominate TikTok, visually simple infographics are common on Facebook and Instagram, and politicized narratives spread rapidly on X. Misinformation policies and detection systems must reflect these distinct formats.

Collaborate with local medical professionals and clinics: Work with regional experts who understand the nuances of language, culture, and local context to better flag and debunk viral falsehoods in local communities. Harness the experts most closely linked to cities and towns, as community members tend to trust the people physically closest to them.

Improve visibility of credible content: Algorithmic incentives often prioritize outrage and emotion. Platforms should enhance the distribution of verified, evidence-based information in Spanish, especially around trending cancer-related stories.

For Cancer Advocacy Groups and NGOs

Engage proactively with viral moments: Celebrity cancer diagnoses and deaths consistently spark massive engagement – including with falsehoods and misleading content. Organizations should prepare content that can provide context, combat falsehoods, and offer support.

Partner with trusted messengers: Among Latino communities in the United States, DDIA research has found that scientists and neighbors are the most trusted stakeholders across partisan lines. Work with doctors, survivors, and caregivers (especially those active in Spanish-speaking communities) to serve as authentic, relatable voices against misinformation.

For Policymakers and Government Health Agencies

Recognize cancer as both a health crisis and a narrative battlefield: Policymakers should work with local universities, community centers, and medical institutions to understand drivers of cancer at the local level and engage communities in proactive conversations.

Support media and digital literacy efforts: Equip communities with the skills to recognize emotional manipulation and pseudo-scientific claims.

METHODOLOGY

To map the spread of cancer-related online harms in Spanish (worldwide), DDIA analyzed public content posted between January 1 and April 1, 2025, across Facebook, Instagram, X, and TikTok.

Using tools like NewsWhip and the Meta Content Library, our team searched for keywords such as “cáncer,” “cancer,” “cánceres,” “cancerígeno,” “tumor,” “tumores,” “quimio,” and “quimioterapia.” These terms helped us capture a broad range of relevant posts in Spanish.

We also pulled all fact-checks referencing “cancer” from the Google Fact-Check API dating back to 2015. This gave us a long-term view of how misinformation about cancer has evolved, and allowed comparisons between English and Spanish content trends.

Next, we focused on engagement metrics (likes, shares, comments, and views) to identify the most influential content (not only those potentially driving misinformation). The results were striking: cancer is not just a medical topic online – it is a highly emotional one.

Facebook and Instagram: During the research period, more than 8,337 Spanish-language posts about cancer “went viral” on Facebook or Instagram, here defined as each surpassing 50,000 interactions – the threshold our team used to classify content as viral on these platforms.

TikTok: On TikTok, in 90 days, 570 cancer-related posts were published in Spanish, generating a combined 11.8 million interactions. That is about 20,700 interactions per post. These figures highlight just how quickly cancer-related narratives can spread online.

X: X was the platform that had the highest volume of Spanish-language cancer content, with over 18,300 unique posts. Our team learned, however, that engagement there is much lower, averaging just 92 interactions per post.

Explore Our Latest Health Reports:

Q4 2023 Snapshot: Health Narratives in Latino Spaces

Want weekly insights on what Latinos are discussing online? Subscribe here